This is something that I've wanted to do for a very long time and had actually intended to do it the past few Octobers but, each time, it always had to be put aside for something else. And, even though I've been on hiatus for a while now, since I didn't want this Halloween to pass without my having done at least post, I decided that now would be a great time as ever to compose this. The reason why I've wanted to do this is because, as a huge fan of horror and science fiction, I've always been fascinated with the artistry and techniques of special effects in all their forms, whether it be highly talented makeup men who turn normal, everyday actors into gruesome monsters or effects wizards who use techniques like stop-motion animation or create life-like animatronics to fool you into believing that what you're seeing is a living, breathing creature. To me, this stuff is as cool as it comes and, since I've loved movie monsters ever since I was a very young kid, I can't put into words how amazing and enchanting it was for me to eventually learn that there have always been people, real Dr. Frankensteins, if you will, whose job it is to create them for movies. I can't pinpoint the exact moment when I realized this but I do know that it was somewhere around the time when I was in middle-school because that's when I remember watching a show on AMC called Cinema Secrets that delved into the magic of special effects, as well as often reading an enormous book on the subject that I came across at my school's library. Plus, that was when I was really beginning to get into the documentaries and special features on movies that I would sometimes find on certain VHS releases of various films like the 25th anniversary edition of Jaws and the 20th anniversary edition of Halloween (which was the first of several different releases of that movie I've owned over the years). Once I got my first DVD player when I was 15 and began to really seek out special editions of movies that I had already owned and loved, as well as ones I had never seen before, my fascination with the artistry and techniques of effects only intensified and as the years passed and I accrued more information, whether it be from those special features or from various book on the subject, I began to learn the names of the big stars of this aspect of filmmaking, from the legends like Jack Pierce, Willis O'Brien, and Ray Harryhausen, to modern masters of the craft like Rick Baker, Stan Winston, and so on. Again, I thought it was so awesome that there were people out there who actually created movie monsters and other creatures for a living. While it didn't inspire me to pursue that type of career (I don't have the type of drive or motivation it takes for that) I still thought that that has to be the coolest job ever and I still do, although I have also learned how cruel and unforgiving the film business can sometimes be, which will come up a few times in this article.

This is something that I've wanted to do for a very long time and had actually intended to do it the past few Octobers but, each time, it always had to be put aside for something else. And, even though I've been on hiatus for a while now, since I didn't want this Halloween to pass without my having done at least post, I decided that now would be a great time as ever to compose this. The reason why I've wanted to do this is because, as a huge fan of horror and science fiction, I've always been fascinated with the artistry and techniques of special effects in all their forms, whether it be highly talented makeup men who turn normal, everyday actors into gruesome monsters or effects wizards who use techniques like stop-motion animation or create life-like animatronics to fool you into believing that what you're seeing is a living, breathing creature. To me, this stuff is as cool as it comes and, since I've loved movie monsters ever since I was a very young kid, I can't put into words how amazing and enchanting it was for me to eventually learn that there have always been people, real Dr. Frankensteins, if you will, whose job it is to create them for movies. I can't pinpoint the exact moment when I realized this but I do know that it was somewhere around the time when I was in middle-school because that's when I remember watching a show on AMC called Cinema Secrets that delved into the magic of special effects, as well as often reading an enormous book on the subject that I came across at my school's library. Plus, that was when I was really beginning to get into the documentaries and special features on movies that I would sometimes find on certain VHS releases of various films like the 25th anniversary edition of Jaws and the 20th anniversary edition of Halloween (which was the first of several different releases of that movie I've owned over the years). Once I got my first DVD player when I was 15 and began to really seek out special editions of movies that I had already owned and loved, as well as ones I had never seen before, my fascination with the artistry and techniques of effects only intensified and as the years passed and I accrued more information, whether it be from those special features or from various book on the subject, I began to learn the names of the big stars of this aspect of filmmaking, from the legends like Jack Pierce, Willis O'Brien, and Ray Harryhausen, to modern masters of the craft like Rick Baker, Stan Winston, and so on. Again, I thought it was so awesome that there were people out there who actually created movie monsters and other creatures for a living. While it didn't inspire me to pursue that type of career (I don't have the type of drive or motivation it takes for that) I still thought that that has to be the coolest job ever and I still do, although I have also learned how cruel and unforgiving the film business can sometimes be, which will come up a few times in this article.What this post is going to consist of is just me talking about a number of people that I feel contributed significantly to the artistry of special effects, be it in regards to makeup or mechanical techniques like stop-motion and animatronics, in horror and science fiction films (particularly the former, since it's October). Some of them are considered true legends, groundbreakers, and innovators in the field, while others can be seen as just guys who are really skilled, hard-working artists who do their job well. Some of them had in their lifetimes or still continue to have flourishing careers, while others were eventually chewed up and spat out by the Hollywood machine and faded into obscurity when they were unable, or unwilling, in some cases, to change with the times. But, regardless, these are the guys that I feel are the absolute cream of the crop when it comes to making unforgettable movie monsters and allowing you to believe the impossible. And, on that note, I have to mention that I'm obviously not going to talk about every single effects artist who ever lived on here, because that would be impossible and, again, these are the ones whose work I personally admire and enjoy. So, if you don't see one of your favorites on here, don't get upset, aside from it being my opinion, it could also be that I simply didn't think of them or haven't seen enough of their work to consider them all that noteworthy.

Interestingly enough, the man who can be considered the first name in the history of effects artistry in terms of makeup was also the first major star of the silver screen: the legendary Lon Chaney. Besides being a well-regarded, versatile actor who was very skilled at pantomime due to both of his parents having been deaf, Chaney was also very talented in using makeup and similar techniques to drastically change his appearance from film to film, earning the nickname The Man With A Thousand Faces and prompting the popular phrase, "Don't step on that spider! It might be Lon Chaney!" Since actors back then did their own makeup, Chaney came up with the various methods of changing his appearance himself, apparently keeping a majority of them in a leather bag that he always carried around with him in Hollywood. When you read up about Chaney, you quickly realize that his reasons for doing so, besides the artistic one, was because he was a very private man and wanted to create a shroud of mystery and anonymity with both the public and the press and once said that, "Between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney" (indeed, he rarely gave interviews and often refused to show his real face even in studio publicity films). As has often been reported, Chaney typically put himself through a lot of pain in order to create these characters. For The Hunchback of Notre Dame, he not only wore a huge hump of plaster in order to create the illusion of a true hunchback but he buried his right eye under a lot of makeup to simulate a growth that was described in the original Victor Hugo novel, which eventually resulted in him being short-sighted for the rest of his life. For the role of Erik in The Phantom of the Opera, Chaney apparently pulled the tip of his nose up with wire and put black paint around his nostrils in order to make them seem larger than they already were, used similar techniques to black out his eyes and make his face look more skull-like, and put nasty, false teeth into his mouth as well. By many accounts, the makeup he created for the famous lost film London After Midnight was especially grueling since it involved some large, shark-like teeth that Chaney put in his mouth as well as pulling down his eyes with wire-like monocles. But most painful of all had to have been what he wore in the film The Penalty, where he played a gangster who's missing both of his legs. To simulate amputated legs, Chaney sat on two wooden buckets with his knees and used leather straps to tie the rest of his legs back. Can you imagine how painful that must have been? The studio doctors actually advised him not to do it but Chaney stuck to his guns and suffered for his career. The fact that he was able to give a performance while in so much pain is what really astounds me. By the way, the reason I keep saying "apparently" and "by many accounts" is because Chaney kept a lot of his memorable makeup techniques away from the press in order to maintain the illusion and mystery of the characters he played, so the accounts that you do read and hear are mostly secondhand accounts that may or may not be true. Indeed, I've read many different stories about how Chaney created some of these makeups, particularly in the role of Erik the Phantom (although Chaney himself did describe the technique he used for The Penalty), so you have to be careful about what you choose to believe. But, regardless as to how he did it exactly, there's no doubt that audiences at the time were amazed at Chaney's ability to change so drastically and, little did he know that, by doing so, he was beginning a huge snowball effect that would grow steadily throughout the years and inspire a lot of talented people.

Interestingly enough, the man who can be considered the first name in the history of effects artistry in terms of makeup was also the first major star of the silver screen: the legendary Lon Chaney. Besides being a well-regarded, versatile actor who was very skilled at pantomime due to both of his parents having been deaf, Chaney was also very talented in using makeup and similar techniques to drastically change his appearance from film to film, earning the nickname The Man With A Thousand Faces and prompting the popular phrase, "Don't step on that spider! It might be Lon Chaney!" Since actors back then did their own makeup, Chaney came up with the various methods of changing his appearance himself, apparently keeping a majority of them in a leather bag that he always carried around with him in Hollywood. When you read up about Chaney, you quickly realize that his reasons for doing so, besides the artistic one, was because he was a very private man and wanted to create a shroud of mystery and anonymity with both the public and the press and once said that, "Between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney" (indeed, he rarely gave interviews and often refused to show his real face even in studio publicity films). As has often been reported, Chaney typically put himself through a lot of pain in order to create these characters. For The Hunchback of Notre Dame, he not only wore a huge hump of plaster in order to create the illusion of a true hunchback but he buried his right eye under a lot of makeup to simulate a growth that was described in the original Victor Hugo novel, which eventually resulted in him being short-sighted for the rest of his life. For the role of Erik in The Phantom of the Opera, Chaney apparently pulled the tip of his nose up with wire and put black paint around his nostrils in order to make them seem larger than they already were, used similar techniques to black out his eyes and make his face look more skull-like, and put nasty, false teeth into his mouth as well. By many accounts, the makeup he created for the famous lost film London After Midnight was especially grueling since it involved some large, shark-like teeth that Chaney put in his mouth as well as pulling down his eyes with wire-like monocles. But most painful of all had to have been what he wore in the film The Penalty, where he played a gangster who's missing both of his legs. To simulate amputated legs, Chaney sat on two wooden buckets with his knees and used leather straps to tie the rest of his legs back. Can you imagine how painful that must have been? The studio doctors actually advised him not to do it but Chaney stuck to his guns and suffered for his career. The fact that he was able to give a performance while in so much pain is what really astounds me. By the way, the reason I keep saying "apparently" and "by many accounts" is because Chaney kept a lot of his memorable makeup techniques away from the press in order to maintain the illusion and mystery of the characters he played, so the accounts that you do read and hear are mostly secondhand accounts that may or may not be true. Indeed, I've read many different stories about how Chaney created some of these makeups, particularly in the role of Erik the Phantom (although Chaney himself did describe the technique he used for The Penalty), so you have to be careful about what you choose to believe. But, regardless as to how he did it exactly, there's no doubt that audiences at the time were amazed at Chaney's ability to change so drastically and, little did he know that, by doing so, he was beginning a huge snowball effect that would grow steadily throughout the years and inspire a lot of talented people.

One of those who followed in Chaney's wake was a Greek immigrant named Jack Pierce, who began working in the fledgling motion picture industry in the 1910's and did everything from acting as an assistant director to a stuntman and an actual actor before he finally found his niche at Universal's makeup department. A 1926 film called The Monkey Talks was his first major makeup assignment, in which he turned actor Jacques Lernier into an ape, and he followed that up with The Man Who Laughs, giving Conrad Veidt an unforgettable permanent grin that would eventually inspire the look of the Joker. It was after that film that Pierce was made the head of Universal's makeup department and, as sad as it is, the 1930 death of Lon Chaney was actually quite fortuitous for Pierce since it ensured that he would be able to create his own makeups for horror films, which were becoming increasingly popular due to Chaney's work, rather than having to step aside and let the Man of a Thousand Faces continue to make himself up. The fact that it was soon decided that actual makeup artists should work on the films rather than continue to allow the actors themselves to do it didn't hurt either. While he wasn't able to do much on Dracula since Bela Lugosi, having come straight from the stage, insisted on doing his own makeup, he was able to create some memorable-looking vampire brides for the count as well as give Lugosi a widow's peak toupee, a look that would become Pierce's personal trademark. That same year, however, Pierce forever made his mark on movie history with his absolutely iconic design of the Frankenstein monster. What more can I say about the look of Boris Karloff in that classic 1931 film that hasn't already been said and praised time and time again? It truly is one of the most legendary character designs to come out of the movies, right up there with other monsters like King Kong and Godzilla. It's such an amazing look that, even if Pierce had never worked again after Frankenstein, it would have still been enough to ensure that he would have gone down in history as one of the greatest artists to ever work in the film business. Enough said.

One of those who followed in Chaney's wake was a Greek immigrant named Jack Pierce, who began working in the fledgling motion picture industry in the 1910's and did everything from acting as an assistant director to a stuntman and an actual actor before he finally found his niche at Universal's makeup department. A 1926 film called The Monkey Talks was his first major makeup assignment, in which he turned actor Jacques Lernier into an ape, and he followed that up with The Man Who Laughs, giving Conrad Veidt an unforgettable permanent grin that would eventually inspire the look of the Joker. It was after that film that Pierce was made the head of Universal's makeup department and, as sad as it is, the 1930 death of Lon Chaney was actually quite fortuitous for Pierce since it ensured that he would be able to create his own makeups for horror films, which were becoming increasingly popular due to Chaney's work, rather than having to step aside and let the Man of a Thousand Faces continue to make himself up. The fact that it was soon decided that actual makeup artists should work on the films rather than continue to allow the actors themselves to do it didn't hurt either. While he wasn't able to do much on Dracula since Bela Lugosi, having come straight from the stage, insisted on doing his own makeup, he was able to create some memorable-looking vampire brides for the count as well as give Lugosi a widow's peak toupee, a look that would become Pierce's personal trademark. That same year, however, Pierce forever made his mark on movie history with his absolutely iconic design of the Frankenstein monster. What more can I say about the look of Boris Karloff in that classic 1931 film that hasn't already been said and praised time and time again? It truly is one of the most legendary character designs to come out of the movies, right up there with other monsters like King Kong and Godzilla. It's such an amazing look that, even if Pierce had never worked again after Frankenstein, it would have still been enough to ensure that he would have gone down in history as one of the greatest artists to ever work in the film business. Enough said.

Pierce's career went into overdrive after the enormous success of Frankenstein. Save for the Invisible Man, which was a created via a combination of optical and physical effects rather than makeup, he proceeded to create the look of every single iconic Universal monster in the 1930's and 40's, from the Mummy to the Bride of Frankenstein and the Wolf man, as well as lesser known creepy characters like Bela Lugosi's role of Dr. Mirakle in Murders in the Rue Morgue and Boris Karloff's devil worshipper character of Poelzig in The Black Cat as well as the disfigured gangster he played in The Raven. Around this time, Universal also loaned Pierce out to the independent production White Zombie, another film starring Lugosi. Needless to say, Pierce was a very busy man around this time and, by all accounts, seemed to really relish the idea that he was the one that created all of these iconic characters, always wearing a surgeon's outfit while working as if he actually was Dr. Frankenstein. What's even more amazing than the fact that one man created all of these legendary character designs is that he did so using very simple techniques and materials like cotton, collodion, spirit gum, yak hair, and nose putty. However, while Pierce may have enjoyed and preferred using these "out of the kit" makeup techniques, the actors who had to endure them weren't too thrilled since the makeups took a long time to apply and were often rather uncomfortable, especially when it came to the collodion, which is a very strong-smelling liquid plastic. Boris Karloff had it very close to his eyes in both the Frankenstein monster and Mummy makeups, which had to have been really arduous for him, and in his makeup for the Wolf Man, Lon Chaney Jr. had to endure itchy yak hair being glued around his face and on his head (small wonder why, after Werewolf of London, Henry Hull decided that he wasn't going to put himself through another makeup process). These uncomfortable, long, tedious makeup jobs, coupled with Pierce's rather stern, hot-tempered, and perfectionist personality, led to him not being too popular with many of the actors who worked with him. Elsa Lanchester, who played the Bride of Frankenstein, said that Pierce never said a single thing to her during the many hours she spent in his makeup chair and also complained about how he insisted on meticulously applying a scar to the underside of her lower jaw that you barely see in the finished film. Lon Chaney Jr. absolutely despised Pierce, which sucked for him because he did a lot of movies with him. He complained about how arduous the makeup process was, how Pierce made things over-complicated with the sticky appliances he glued to his face, and even claimed that he intentionally burned him with a hot curling iron whenever they had an argument (when it comes to the latter claim, keep in mind that Chaney had a habit of making stuff up as well as a reputation of being a hellraiser on and off the set). It also didn't help that Chaney had a nasty allergic reaction to the makeup he had to wear for the monster in The Ghost of Frankenstein and had to endure eight hours of being wrapped up in bandages for the three times he played Kharis the mummy, a role that he hated anyway. It may not have been a happy collaboration between Chaney and Pierce but, nevertheless, they created some memorable monsters together (the monsters were, often, the only memorable thing about the movie they worked on) and the same goes for everyone else Pierce, worked with, especially Karloff. In fact, Karloff had nothing but praise for Pierce, often saying that he owed him everything and even called him the best makeup man in the world. But then again, nobody had anything bad to say about Karloff himself, so even cranky old Pierce probably couldn't help but become fond of him. (I don't know what Lugosi's opinion of him was but I do know that playing the Frankenstein monster in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man was not at all comfortable for him.)

Pierce's career went into overdrive after the enormous success of Frankenstein. Save for the Invisible Man, which was a created via a combination of optical and physical effects rather than makeup, he proceeded to create the look of every single iconic Universal monster in the 1930's and 40's, from the Mummy to the Bride of Frankenstein and the Wolf man, as well as lesser known creepy characters like Bela Lugosi's role of Dr. Mirakle in Murders in the Rue Morgue and Boris Karloff's devil worshipper character of Poelzig in The Black Cat as well as the disfigured gangster he played in The Raven. Around this time, Universal also loaned Pierce out to the independent production White Zombie, another film starring Lugosi. Needless to say, Pierce was a very busy man around this time and, by all accounts, seemed to really relish the idea that he was the one that created all of these iconic characters, always wearing a surgeon's outfit while working as if he actually was Dr. Frankenstein. What's even more amazing than the fact that one man created all of these legendary character designs is that he did so using very simple techniques and materials like cotton, collodion, spirit gum, yak hair, and nose putty. However, while Pierce may have enjoyed and preferred using these "out of the kit" makeup techniques, the actors who had to endure them weren't too thrilled since the makeups took a long time to apply and were often rather uncomfortable, especially when it came to the collodion, which is a very strong-smelling liquid plastic. Boris Karloff had it very close to his eyes in both the Frankenstein monster and Mummy makeups, which had to have been really arduous for him, and in his makeup for the Wolf Man, Lon Chaney Jr. had to endure itchy yak hair being glued around his face and on his head (small wonder why, after Werewolf of London, Henry Hull decided that he wasn't going to put himself through another makeup process). These uncomfortable, long, tedious makeup jobs, coupled with Pierce's rather stern, hot-tempered, and perfectionist personality, led to him not being too popular with many of the actors who worked with him. Elsa Lanchester, who played the Bride of Frankenstein, said that Pierce never said a single thing to her during the many hours she spent in his makeup chair and also complained about how he insisted on meticulously applying a scar to the underside of her lower jaw that you barely see in the finished film. Lon Chaney Jr. absolutely despised Pierce, which sucked for him because he did a lot of movies with him. He complained about how arduous the makeup process was, how Pierce made things over-complicated with the sticky appliances he glued to his face, and even claimed that he intentionally burned him with a hot curling iron whenever they had an argument (when it comes to the latter claim, keep in mind that Chaney had a habit of making stuff up as well as a reputation of being a hellraiser on and off the set). It also didn't help that Chaney had a nasty allergic reaction to the makeup he had to wear for the monster in The Ghost of Frankenstein and had to endure eight hours of being wrapped up in bandages for the three times he played Kharis the mummy, a role that he hated anyway. It may not have been a happy collaboration between Chaney and Pierce but, nevertheless, they created some memorable monsters together (the monsters were, often, the only memorable thing about the movie they worked on) and the same goes for everyone else Pierce, worked with, especially Karloff. In fact, Karloff had nothing but praise for Pierce, often saying that he owed him everything and even called him the best makeup man in the world. But then again, nobody had anything bad to say about Karloff himself, so even cranky old Pierce probably couldn't help but become fond of him. (I don't know what Lugosi's opinion of him was but I do know that playing the Frankenstein monster in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man was not at all comfortable for him.) Pierce's personality is what ultimately led to him being fired as the head of Universal's makeup department. Besides his being a rather stern and cranky curmudgeon, his stubbornness and refusal to adapt to new techniques involving foam latex, which was easier and quicker to apply and more comfortable for actors, put him at odds with the regime that took Universal over in the late 40's. He had relented a few times and used a rubber headpiece for the Frankenstein monster in The Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein as well as a latex nose for the Wolf Man but, regardless, he mostly stuck to his traditional, "out of the kit" techniques while, throughout the 40's, foam latex and rubber were starting to become the norm. When the aforementioned new regime took over at Universal, they were eager to employ this easier, more cost-effective (that's the keyword right there) method and when Pierce refused to do so, he was fired from his position. From that point on, Pierce worked as a free-lancer on mostly low-budget, independent films like Slave Girl, The Brain from Planet Arous, and Teenage Monster, as well as on TV shows like You Are There, Telephone Time, and most notably, Mister Ed, which would prove to be his last gig. While he had a very happy reunion with his old pal Boris Karloff on an episode of This Is Your Life devoted to the actor (which is what this paragraph's image is from), the last couple of decades of Pierce's life were not a joyous time for him since he rode them out in virtual obscurity, no longer able to do the inspired monster makeups he did so well. Yes, Mister Ed was a popular TV show but what could he have done there besides applying straight makeup to the actors and perhaps manipulating the horse's lips to make it look like he was talking? Sad. When he died in 1968 at the age of 79, almost no one batted eyebrow. Fortunately, though, Pierce has been redeemed through history, with makeup legends like Rick Baker and Tom Savini (whom we'll be talking about later) citing him as inspirations for their own amazing work and making people aware that Pierce deserves all of the credit and admiration he can get because, with all due respect to Lon Chaney, he truly was the father of movie monster makeup.

Pierce's personality is what ultimately led to him being fired as the head of Universal's makeup department. Besides his being a rather stern and cranky curmudgeon, his stubbornness and refusal to adapt to new techniques involving foam latex, which was easier and quicker to apply and more comfortable for actors, put him at odds with the regime that took Universal over in the late 40's. He had relented a few times and used a rubber headpiece for the Frankenstein monster in The Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein as well as a latex nose for the Wolf Man but, regardless, he mostly stuck to his traditional, "out of the kit" techniques while, throughout the 40's, foam latex and rubber were starting to become the norm. When the aforementioned new regime took over at Universal, they were eager to employ this easier, more cost-effective (that's the keyword right there) method and when Pierce refused to do so, he was fired from his position. From that point on, Pierce worked as a free-lancer on mostly low-budget, independent films like Slave Girl, The Brain from Planet Arous, and Teenage Monster, as well as on TV shows like You Are There, Telephone Time, and most notably, Mister Ed, which would prove to be his last gig. While he had a very happy reunion with his old pal Boris Karloff on an episode of This Is Your Life devoted to the actor (which is what this paragraph's image is from), the last couple of decades of Pierce's life were not a joyous time for him since he rode them out in virtual obscurity, no longer able to do the inspired monster makeups he did so well. Yes, Mister Ed was a popular TV show but what could he have done there besides applying straight makeup to the actors and perhaps manipulating the horse's lips to make it look like he was talking? Sad. When he died in 1968 at the age of 79, almost no one batted eyebrow. Fortunately, though, Pierce has been redeemed through history, with makeup legends like Rick Baker and Tom Savini (whom we'll be talking about later) citing him as inspirations for their own amazing work and making people aware that Pierce deserves all of the credit and admiration he can get because, with all due respect to Lon Chaney, he truly was the father of movie monster makeup.  Pierce was replaced as the head of the makeup department by Bud Westmore, a guy who came from family that has a long history in the move makeup business, with his father, George, having been an in-demand wigmaker and hairdresser who actually found the industry's first makeup department, and his three brothers having worked at major studios throughout their respective careers and contributed to movies like Paramount's 1931 film of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Gone With The Wind. Bud himself has over 450 film and television shows on his resume and, unlike his predecessor, did as he was told and used foam rubber and latex appliances for their science fiction and horror movies, starting with the ones he made for the Frankenstein monster and the Wolf Man in Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein. However, despite his long and successful career, which his tenure at Universal lasting until 1971, I don't know if I should talk about him that much or give him too much credit, since from everything I've read, he took full credit for a lot of things he didn't have much actual involvement with. At that point, it was simply custom for the head of the makeup department to be given sole credit on films and television when, in actuality, there was a large team of people who contributed to the end result onscreen, but regardless, Westmore seems to have also been something of a glory hound, always eager to make sure that the press saw him working on a makeup or creature design whenever they visited the studio, if he really had little input into it. The most notable example involves Creature from the Black Lagoon, which has to be the most well-known monster flick his name was ever attached to. Although Westmore was given sole credit for the iconic monster's design, many who worked on the film, including Ben Chapman who played the Gill-Man whenever he was on land, insisted that Millicent Patrick, a former Disney animator, was the one who really came up with the look of the monster, with Westmore having very little involvement. Indeed, it seems as if Patrick absolutely adored the Gill-Man, thinking of him as her baby, and even toured with a man in the suit in order to promote the film, but her contribution to the film was overshadowed by Westmore. Plus, on his audio commentary for the film, historian Tom Weaver tells a story about how another man involved in the makeup department learned that Westmore was going to try to send home for that day since the press was coming and he, again, wanted to appear to be the sole person behind the makeup and monster effects. And plus, from what I can remember (I only listened to that commentary once and it was years ago), when Westmore couldn't get rid of him, he still made sure that he was in a photograph the press took when they arrived, acting as if he was working on a monster suit when he really wasn't. I don't know if I should give Westmore too much flack for this since, in later years, Stan Winston would unabashedly take full credit for an entire team's work but, at the same time, at least he often admitted that he did so, unlike Westmore. Maybe studio policy at the time wouldn't have allowed him to do it but still,, from everything I've read about him, it doesn't sound like Westmore would have admitted the truth even if he did have the chance. But, regardless, Westmore eventually did become a makeup legend in his own right, with his entire family getting a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and he worked up in the business up until his death of a heart attack at the age of 55 in 1973.

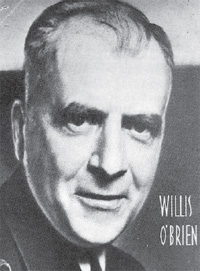

Pierce was replaced as the head of the makeup department by Bud Westmore, a guy who came from family that has a long history in the move makeup business, with his father, George, having been an in-demand wigmaker and hairdresser who actually found the industry's first makeup department, and his three brothers having worked at major studios throughout their respective careers and contributed to movies like Paramount's 1931 film of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Gone With The Wind. Bud himself has over 450 film and television shows on his resume and, unlike his predecessor, did as he was told and used foam rubber and latex appliances for their science fiction and horror movies, starting with the ones he made for the Frankenstein monster and the Wolf Man in Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein. However, despite his long and successful career, which his tenure at Universal lasting until 1971, I don't know if I should talk about him that much or give him too much credit, since from everything I've read, he took full credit for a lot of things he didn't have much actual involvement with. At that point, it was simply custom for the head of the makeup department to be given sole credit on films and television when, in actuality, there was a large team of people who contributed to the end result onscreen, but regardless, Westmore seems to have also been something of a glory hound, always eager to make sure that the press saw him working on a makeup or creature design whenever they visited the studio, if he really had little input into it. The most notable example involves Creature from the Black Lagoon, which has to be the most well-known monster flick his name was ever attached to. Although Westmore was given sole credit for the iconic monster's design, many who worked on the film, including Ben Chapman who played the Gill-Man whenever he was on land, insisted that Millicent Patrick, a former Disney animator, was the one who really came up with the look of the monster, with Westmore having very little involvement. Indeed, it seems as if Patrick absolutely adored the Gill-Man, thinking of him as her baby, and even toured with a man in the suit in order to promote the film, but her contribution to the film was overshadowed by Westmore. Plus, on his audio commentary for the film, historian Tom Weaver tells a story about how another man involved in the makeup department learned that Westmore was going to try to send home for that day since the press was coming and he, again, wanted to appear to be the sole person behind the makeup and monster effects. And plus, from what I can remember (I only listened to that commentary once and it was years ago), when Westmore couldn't get rid of him, he still made sure that he was in a photograph the press took when they arrived, acting as if he was working on a monster suit when he really wasn't. I don't know if I should give Westmore too much flack for this since, in later years, Stan Winston would unabashedly take full credit for an entire team's work but, at the same time, at least he often admitted that he did so, unlike Westmore. Maybe studio policy at the time wouldn't have allowed him to do it but still,, from everything I've read about him, it doesn't sound like Westmore would have admitted the truth even if he did have the chance. But, regardless, Westmore eventually did become a makeup legend in his own right, with his entire family getting a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and he worked up in the business up until his death of a heart attack at the age of 55 in 1973.  Alright, let's get away from makeup for a bit and talk about some major players in other effects occupations, starting off with the man who can be credited as the father of the Hollywood visual effects: Willis O'Brien. He can certainly be considered the father of stop-motion animation (although the technique had existed before he came along), simply stumbling across his immense knack for the technique one day in 1913 when he was fooling around with a newsreel camera and some models that he had sculpted himself. Indeed, while O'Brien had held many different and varied jobs in the early parts of his professional life, he was an artist and accomplished sculptor virtually from the start and when a San Francisco exhibitor came across this little bit of effects footage and commissioned him to make a little film called The Dinosaur and The Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy, it set him off on a path towards the burgeoning film industry. He was soon hired by Thomas Edison to produce some other short, stop-motion films with a similar theme, as well as work on the first films to ever combine the technique with live-action footage, and that would eventually lead him to direct and produce the effects for a movie called The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. However, O'Brien did not get along well with the Herbert Dawley, the man who had commissioned him to create the film, and while the film, which was ultimately cut down to an 11-minute running time rather than the original 45-minute, made a significant amount of money for the time and spawned a sequel, O'Brien received no credit for it whatsoever and also didn't receive much, if any, compensation (sadly, this would end up being simply the first of many times O'Brien would be screwed over in the film industry). But, despite the unhappy working experience, his involvement was enough for Harry Hoyt to hire him to create the effects for The Lost World in 1925, which was the first time when O'Brien really got to strut his stuff and show what he could do. While his stop-motion effects for the film may look very primitive and a bit silly by today's standards or even by those that he would later set in King Kong, at the time they were absolutely mind-boggling and were enough to convince a group of people that it was actual documentary footage of real, living dinosaurs. Although I must admit that I've never actually seen the film myself, I've heard that the effects are by far the most memorable part of it and that, thanks to O'Brien, it could be considered the world's first giant monster movie. And finally, I must admit that, judging from the clips I've seen, those effects sequences are still entertaining to watch despite their primitive aspects.

Alright, let's get away from makeup for a bit and talk about some major players in other effects occupations, starting off with the man who can be credited as the father of the Hollywood visual effects: Willis O'Brien. He can certainly be considered the father of stop-motion animation (although the technique had existed before he came along), simply stumbling across his immense knack for the technique one day in 1913 when he was fooling around with a newsreel camera and some models that he had sculpted himself. Indeed, while O'Brien had held many different and varied jobs in the early parts of his professional life, he was an artist and accomplished sculptor virtually from the start and when a San Francisco exhibitor came across this little bit of effects footage and commissioned him to make a little film called The Dinosaur and The Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy, it set him off on a path towards the burgeoning film industry. He was soon hired by Thomas Edison to produce some other short, stop-motion films with a similar theme, as well as work on the first films to ever combine the technique with live-action footage, and that would eventually lead him to direct and produce the effects for a movie called The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. However, O'Brien did not get along well with the Herbert Dawley, the man who had commissioned him to create the film, and while the film, which was ultimately cut down to an 11-minute running time rather than the original 45-minute, made a significant amount of money for the time and spawned a sequel, O'Brien received no credit for it whatsoever and also didn't receive much, if any, compensation (sadly, this would end up being simply the first of many times O'Brien would be screwed over in the film industry). But, despite the unhappy working experience, his involvement was enough for Harry Hoyt to hire him to create the effects for The Lost World in 1925, which was the first time when O'Brien really got to strut his stuff and show what he could do. While his stop-motion effects for the film may look very primitive and a bit silly by today's standards or even by those that he would later set in King Kong, at the time they were absolutely mind-boggling and were enough to convince a group of people that it was actual documentary footage of real, living dinosaurs. Although I must admit that I've never actually seen the film myself, I've heard that the effects are by far the most memorable part of it and that, thanks to O'Brien, it could be considered the world's first giant monster movie. And finally, I must admit that, judging from the clips I've seen, those effects sequences are still entertaining to watch despite their primitive aspects.  Of course, eight years after The Lost World, O'Brien would surpass himself leaps and bounds and create the absolutely amazing effects for the timeless classic King Kong, not only contributing greatly to what is by and large one of the greatest movies of all time, in addition to one of the greatest monster movies, but also breathing real life into and giving a genuine personality and heart to the title character. In that movie, Kong truly is a creature with a soul and, even though he kills many, many people throughout the film, O'Brien's amazing animation work makes you love and sympathize with him, adding greatly to the tragedy at the end when he's shot down by the airplanes. It's one thing to use stop-motion to make a creature seem alive by moving around and whatnot but if you can use it to make the creature an actual "character" with emotions and feelings that the viewer can latch onto and empathize with, then there is no other word to describe it other than movie magic and that's what Willis O'Brien did with this movie. But, while King Kong was certainly a triumph for O'Brien (or "O'Bie," as his friends and family called him), the luster of it didn't last long. For one, RKO, eager to bank on the enormous success of the film, asked for a sequel to be made as soon, and as cheaply, as possible. The Son of Kong was made on such a low-budget and short schedule that O'Brien was hardly enthusiastic about working on the film, especially since he didn't think the story was that good either. By all accounts, O'Brien had his assistant do most of the animation on the film and even asked to have his name taken off the final film but producer and RKO head of production Merian C. Cooper, who was one of the directors and creators of the original King Kong, wouldn't have it, which led to things being strained between the two men. Things got even worse and became downright tragic for O'Brien during the production when his estranged ex-wife killed their two sons and then tried to take her own life but it ended up being a botched suicide attempt that left her lingering for another year. The photo you see here was taken after that happened and I think you can plainly see that O'Brien was in a lot of pain at the time.

Of course, eight years after The Lost World, O'Brien would surpass himself leaps and bounds and create the absolutely amazing effects for the timeless classic King Kong, not only contributing greatly to what is by and large one of the greatest movies of all time, in addition to one of the greatest monster movies, but also breathing real life into and giving a genuine personality and heart to the title character. In that movie, Kong truly is a creature with a soul and, even though he kills many, many people throughout the film, O'Brien's amazing animation work makes you love and sympathize with him, adding greatly to the tragedy at the end when he's shot down by the airplanes. It's one thing to use stop-motion to make a creature seem alive by moving around and whatnot but if you can use it to make the creature an actual "character" with emotions and feelings that the viewer can latch onto and empathize with, then there is no other word to describe it other than movie magic and that's what Willis O'Brien did with this movie. But, while King Kong was certainly a triumph for O'Brien (or "O'Bie," as his friends and family called him), the luster of it didn't last long. For one, RKO, eager to bank on the enormous success of the film, asked for a sequel to be made as soon, and as cheaply, as possible. The Son of Kong was made on such a low-budget and short schedule that O'Brien was hardly enthusiastic about working on the film, especially since he didn't think the story was that good either. By all accounts, O'Brien had his assistant do most of the animation on the film and even asked to have his name taken off the final film but producer and RKO head of production Merian C. Cooper, who was one of the directors and creators of the original King Kong, wouldn't have it, which led to things being strained between the two men. Things got even worse and became downright tragic for O'Brien during the production when his estranged ex-wife killed their two sons and then tried to take her own life but it ended up being a botched suicide attempt that left her lingering for another year. The photo you see here was taken after that happened and I think you can plainly see that O'Brien was in a lot of pain at the time.

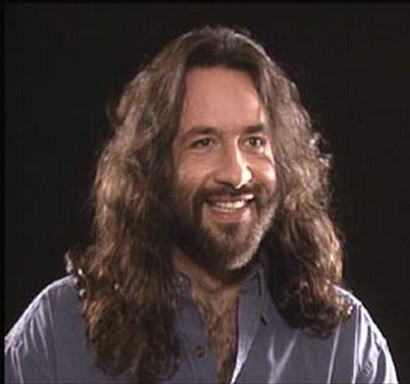

For me, our next subject, Ray Harryhausen, is a prime example of a fan of the genre who strove so hard to work in it and was so talented in his own right that he himself became an innovator and legend in it. Harryhausen often said that after he saw King Kong during its first theatrical release in 1933 (the first of many, many times he saw it), he was never the same. It inspired him to experiment and make little animated shorts with models that he himself sculpted but he really began to hone his talents after he had an arranged meeting with Willis O'Brien, who suggested that he attend classes on graphic arts and sculpture to do so. He was soon hired by producer George Pal to animate a series of shorts known as "Puppetoons" and during World War II, while he served in the Special Services division, he worked on short, animated films about the development of military equipment at his home. He continued to experiment with stop-motion after the war and soon afterward, landed his first major film when he assisted Willis O'Brien on Mighty Joe Young. As I said, while O'Brien received an Oscar for the film, it was actually Harryhausen who did most of the animating, while O'Brien focused on solving the technical problems of the production. After that, Harryhausen embarked on his first solo feature film, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. As had been the case with O'Brien on The Lost World, Harryhausen really got a chance to show what he could do when left to his own devices. Not only is the beast himself an awesome creature, beautifully sculpted and animated by Harryhausen, but it was also on this film that he developed a matting process that very effectively integrated the models with live-action background and foreground elements. The film went on to be an enormous box-office success for Warner Bros. and it was then that Harryhausen's career really took off. After that came It Came from Beneath the Sea, Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, and 20 Million Miles to Earth, all of which were very profitable. Harryhausen said that while most people in Hollywood tried to glamorize the actors, he tried to do the same for the dinosaurs and monsters he created and you can definitely see that when you watch his films since, especially with those I just mentioned, the monsters and effects scenes are what people remember the most from them. Kenneth Tobey and Faith Domergue are alright as the human stars of It Came from Beneath the Sea but, let's face it, you want to see that giant octopus do his thing and when he does, it doesn't disappoint, especially during the climactic attack on San Francisco. The animation he did on the spaceships in Earth vs. The Flying Saucers is something I find especially impressive since he was working with cumbersome models of machines rather than articulated creatures and had to animate not only their flying and moving parts but also the destruction they caused during the attack sequences. And for me personally, the Ymir in 20 Million Miles to Earth is the most sympathetic creature Harryhausen ever did on his own. You really feel bad for this poor thing when he finds himself on a strange planet and is often being chased and attacked by ignorant people who think he's more dangerous than he is, while he himself is unable to stop growing larger every day due to the effect of the atmosphere on him.

For me, our next subject, Ray Harryhausen, is a prime example of a fan of the genre who strove so hard to work in it and was so talented in his own right that he himself became an innovator and legend in it. Harryhausen often said that after he saw King Kong during its first theatrical release in 1933 (the first of many, many times he saw it), he was never the same. It inspired him to experiment and make little animated shorts with models that he himself sculpted but he really began to hone his talents after he had an arranged meeting with Willis O'Brien, who suggested that he attend classes on graphic arts and sculpture to do so. He was soon hired by producer George Pal to animate a series of shorts known as "Puppetoons" and during World War II, while he served in the Special Services division, he worked on short, animated films about the development of military equipment at his home. He continued to experiment with stop-motion after the war and soon afterward, landed his first major film when he assisted Willis O'Brien on Mighty Joe Young. As I said, while O'Brien received an Oscar for the film, it was actually Harryhausen who did most of the animating, while O'Brien focused on solving the technical problems of the production. After that, Harryhausen embarked on his first solo feature film, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. As had been the case with O'Brien on The Lost World, Harryhausen really got a chance to show what he could do when left to his own devices. Not only is the beast himself an awesome creature, beautifully sculpted and animated by Harryhausen, but it was also on this film that he developed a matting process that very effectively integrated the models with live-action background and foreground elements. The film went on to be an enormous box-office success for Warner Bros. and it was then that Harryhausen's career really took off. After that came It Came from Beneath the Sea, Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, and 20 Million Miles to Earth, all of which were very profitable. Harryhausen said that while most people in Hollywood tried to glamorize the actors, he tried to do the same for the dinosaurs and monsters he created and you can definitely see that when you watch his films since, especially with those I just mentioned, the monsters and effects scenes are what people remember the most from them. Kenneth Tobey and Faith Domergue are alright as the human stars of It Came from Beneath the Sea but, let's face it, you want to see that giant octopus do his thing and when he does, it doesn't disappoint, especially during the climactic attack on San Francisco. The animation he did on the spaceships in Earth vs. The Flying Saucers is something I find especially impressive since he was working with cumbersome models of machines rather than articulated creatures and had to animate not only their flying and moving parts but also the destruction they caused during the attack sequences. And for me personally, the Ymir in 20 Million Miles to Earth is the most sympathetic creature Harryhausen ever did on his own. You really feel bad for this poor thing when he finds himself on a strange planet and is often being chased and attacked by ignorant people who think he's more dangerous than he is, while he himself is unable to stop growing larger every day due to the effect of the atmosphere on him.  I must confess that I've never watched any of Harryhausen's fantasy films, like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, The Three Worlds of Gulliver, Mysterious Island, and Jason and the Argonauts, simply because epic fantasy has never been my cup of tea (no, I'm not a fan of Lord of the Rings either). I probably will watch them at some point since I'm such a fan of Harryhausen's monster movies and because everything I've seen from those movies, especially the legendary skeleton battle scene in Jason and the Argonauts (that must have been a bitch to animate with all of those different models), looks amazing but, for right now, I can't say much about them other than that. Another movie of his that I can't really say much about is The Valley of Gwangi. I have seen that but it was many, many years ago and I don't remember much about it, save for the animation on the dinosaurs, especially Gwangi himself, being excellent and that there was also a very well-animated and cute miniature horse at the beginning of the film. By the way, when I describe these films as being Harryhausen's, I'm not saying that just because he himself did the special effects for them but because, even though they had "official" directors behind them, he really was the major creative force behind them. He was involved in the story development, art direction, storyboards, and even in deciding on the general tone of the films, which were conditions that any actual director of them had to work with. And since he did everything himself, he not only saved the studios money but also further ensured that the films, especially the effects scenes, can truly be considered his work. I think it's safe to say that he had the career that Willis O'Brien unsuccessfully strove for his entire life, don't you? But, unlike O'Brien, Harryhausen never won on Oscar for his work, with the reason being that he moved to London in 1960 and did all of his work from then on out in Europe. And, as they say, nothing lasts for ever. As the 1970's came around, Harryhausen began to find less and less work, with The Golden Voyage of Sinbad and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger being the only two films he produced during the decade. His last film was the big-budget Clash of the Titans, which was so enormous that it was the one time when he had to have help from assistants. While the film did well at the box-office, by that point more sophisticated and realistic special effects techniques were being developed in Hollywood and when the studios passed on a proposed sequel to Clash of the Titans, Harryhausen decided to retire. As his friend Ray Bradbury once said, I think he stopped at the right time too because, from what I've seen of that film (the Kraken... wow!), it's unlikely he would have topped that. But, despite his retirement, Harryhausen's legend and legacy continued to grow over the last 30 plus years of his life, as he realized just how many people he had inspired with his amazing work and also accrued a number of honorary awards. He was almost always on hand to talk about his various films and the movies that inspired him, like King Kong, and he had a hand in the restoration of his movies when they were put on DVD and Blu-Ray. That's something else he managed to experience during his lifetime that O'Brien never did: recognition and praise for his accomplishments. While I was certainly sad to hear of his death at the age of 92 in 2013, I was happy that he went to his grave after having had a long, fruitful life and had garnered all of the admiration that he so richly deserved.

I must confess that I've never watched any of Harryhausen's fantasy films, like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, The Three Worlds of Gulliver, Mysterious Island, and Jason and the Argonauts, simply because epic fantasy has never been my cup of tea (no, I'm not a fan of Lord of the Rings either). I probably will watch them at some point since I'm such a fan of Harryhausen's monster movies and because everything I've seen from those movies, especially the legendary skeleton battle scene in Jason and the Argonauts (that must have been a bitch to animate with all of those different models), looks amazing but, for right now, I can't say much about them other than that. Another movie of his that I can't really say much about is The Valley of Gwangi. I have seen that but it was many, many years ago and I don't remember much about it, save for the animation on the dinosaurs, especially Gwangi himself, being excellent and that there was also a very well-animated and cute miniature horse at the beginning of the film. By the way, when I describe these films as being Harryhausen's, I'm not saying that just because he himself did the special effects for them but because, even though they had "official" directors behind them, he really was the major creative force behind them. He was involved in the story development, art direction, storyboards, and even in deciding on the general tone of the films, which were conditions that any actual director of them had to work with. And since he did everything himself, he not only saved the studios money but also further ensured that the films, especially the effects scenes, can truly be considered his work. I think it's safe to say that he had the career that Willis O'Brien unsuccessfully strove for his entire life, don't you? But, unlike O'Brien, Harryhausen never won on Oscar for his work, with the reason being that he moved to London in 1960 and did all of his work from then on out in Europe. And, as they say, nothing lasts for ever. As the 1970's came around, Harryhausen began to find less and less work, with The Golden Voyage of Sinbad and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger being the only two films he produced during the decade. His last film was the big-budget Clash of the Titans, which was so enormous that it was the one time when he had to have help from assistants. While the film did well at the box-office, by that point more sophisticated and realistic special effects techniques were being developed in Hollywood and when the studios passed on a proposed sequel to Clash of the Titans, Harryhausen decided to retire. As his friend Ray Bradbury once said, I think he stopped at the right time too because, from what I've seen of that film (the Kraken... wow!), it's unlikely he would have topped that. But, despite his retirement, Harryhausen's legend and legacy continued to grow over the last 30 plus years of his life, as he realized just how many people he had inspired with his amazing work and also accrued a number of honorary awards. He was almost always on hand to talk about his various films and the movies that inspired him, like King Kong, and he had a hand in the restoration of his movies when they were put on DVD and Blu-Ray. That's something else he managed to experience during his lifetime that O'Brien never did: recognition and praise for his accomplishments. While I was certainly sad to hear of his death at the age of 92 in 2013, I was happy that he went to his grave after having had a long, fruitful life and had garnered all of the admiration that he so richly deserved.

Of course, it was not long after he returned to Toho that Tsuburaya was able to fulfill his dream of making his own monster movie with the production of Godzilla. In fact, when he first set to work on the film, he intended to use stop-motion effects in tribute to the love and admiration he had for King Kong but, unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on how you look at it), time, budget, and technical knowhow made it impossible to do so. But, instead of giving up, Tsuburaya used his talent and imagination to come with another way to visualize a giant monster destroying a city and ultimately decided on using an actor in a rubber suit on a miniature set, pioneering the technique now known as "suitmation." As I've said countless times before, while the effects in the original Godzilla might not be the most realistic, they're still very awesome and imaginative in their own way and are a strong testament to what you can do with a little ingenuity. Plus, I think they're just as well-executed and groundbreaking as those in King Kong, but that's just me. Feel free to disagree. Anyway, the enormous success of Godzilla ensured that Tsuburaya would have a long and fruitful career ahead of him as Japan's top effect maestro. Never one to rest on his laurels, Tsuburaya continued to innovate from movie to movie, creating Japan's first optical printer and putting it to work soon afterward, continually refining the tricky matting process, dabbling in stop-motion a few times, having his crews create more detailed and intricately-designed miniatures, and facing the challenges of staging and filming big monster brawls. There may have been some stumbling blocks along the way, like the very cheap-looking and unconvincing puppets used for close-ups of the various monsters' heads early on, the unintended instances of extremely fast movement during Godzilla and Anguirus' big fight in Osaka in Godzilla Raids Again, the utterly fake-looking dolls for some shots of the Shobijin in Mothra, and the pretty bad matting effects in King Kong vs. Godzilla (not to mention the atrocious design of the Kong suit in that film), but overall, the films were almost always very well put together and the improvement of the effects work as time went on was very noticeable. By the time you get into the mid-60's with movies like Godzilla vs. Monster Zero and War of the Gargantuas, the effects are unreal in terms of how awesome they look. However, after Monster Zero, Tsuburaya was no longer the actual special effects director on the Godzilla movies since he was running his own visual effects studio, Tsuburaya Productions, which worked mainly in television. They put out three television shows in 1966 alone, including the first iterations of Ultraman. Also, since the budgets of the Godzilla movies were beginning to be cut down to make up for diminishing box-office returns, Tsuburaya decided to let his assistant, Sadamasa Arikawa, handle the direction of the effects there while he focused on bigger movies like the aforementioned War of the Gargantuas and King Kong Escapes.

Of course, it was not long after he returned to Toho that Tsuburaya was able to fulfill his dream of making his own monster movie with the production of Godzilla. In fact, when he first set to work on the film, he intended to use stop-motion effects in tribute to the love and admiration he had for King Kong but, unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on how you look at it), time, budget, and technical knowhow made it impossible to do so. But, instead of giving up, Tsuburaya used his talent and imagination to come with another way to visualize a giant monster destroying a city and ultimately decided on using an actor in a rubber suit on a miniature set, pioneering the technique now known as "suitmation." As I've said countless times before, while the effects in the original Godzilla might not be the most realistic, they're still very awesome and imaginative in their own way and are a strong testament to what you can do with a little ingenuity. Plus, I think they're just as well-executed and groundbreaking as those in King Kong, but that's just me. Feel free to disagree. Anyway, the enormous success of Godzilla ensured that Tsuburaya would have a long and fruitful career ahead of him as Japan's top effect maestro. Never one to rest on his laurels, Tsuburaya continued to innovate from movie to movie, creating Japan's first optical printer and putting it to work soon afterward, continually refining the tricky matting process, dabbling in stop-motion a few times, having his crews create more detailed and intricately-designed miniatures, and facing the challenges of staging and filming big monster brawls. There may have been some stumbling blocks along the way, like the very cheap-looking and unconvincing puppets used for close-ups of the various monsters' heads early on, the unintended instances of extremely fast movement during Godzilla and Anguirus' big fight in Osaka in Godzilla Raids Again, the utterly fake-looking dolls for some shots of the Shobijin in Mothra, and the pretty bad matting effects in King Kong vs. Godzilla (not to mention the atrocious design of the Kong suit in that film), but overall, the films were almost always very well put together and the improvement of the effects work as time went on was very noticeable. By the time you get into the mid-60's with movies like Godzilla vs. Monster Zero and War of the Gargantuas, the effects are unreal in terms of how awesome they look. However, after Monster Zero, Tsuburaya was no longer the actual special effects director on the Godzilla movies since he was running his own visual effects studio, Tsuburaya Productions, which worked mainly in television. They put out three television shows in 1966 alone, including the first iterations of Ultraman. Also, since the budgets of the Godzilla movies were beginning to be cut down to make up for diminishing box-office returns, Tsuburaya decided to let his assistant, Sadamasa Arikawa, handle the direction of the effects there while he focused on bigger movies like the aforementioned War of the Gargantuas and King Kong Escapes. Sadly, by the end of the 60's, Tsuburaya's involvement with the film and television industry, including with his own company, rapidly dwindled as he became more and more ill from cancer. While he's credited as special effects director and supervisor on movies like Destroy All Monsters and Godzilla's Revenge, those credits were actually out of respect and he really had very little involvement with those movies. The 1969 film Latitude Zero was the last science fiction film Tsuburaya worked on. Ironically, it wasn't the cancer that killed him but rather a sudden heart attack that he had while on vacation with his family in January of 1970. He was 68. His death was a huge blow to the Japanese film industry and the Godzilla franchise in particular, with suit-actor Haruo Nakajima losing his enthusiasm for the job and retiring shortly afterward and with director Ishiro Honda feeling that the series should have died with Tsuburaya. While the series definitely survived and thrived long after the death of Tsuburaya, it took a while for the quality of the effects (and some would argue the movies themselves due to the dwindling budgets) to recover. Fortunately, though, Tsuburaya had some really talented successors in Teruyoshi Nakano and Koichi Kawakita, who kept the series alive and continued to build upon their sensei's pioneering techniques throughout their respective careers. Ultimately, while the Godzilla movies and Japanese sci-fi movies in general have often been mocked for having "laughable" special effects, I'm glad that people have lately been recognizing the imagination, ingenuity, and craftsmanship that went into these films, especially the original Godzilla, and that this trend will continue for years to come because Eiji Tsuburaya deserves to be lauded just as much as his more famous American contemporaries.

Going back to makeup for a bit, I feel like I must give credit to a couple of guys whom I've never heard mentioned or discussed in any major way save for a couple of fleeting acknowledgements. I'm talking Philip Leakey and Roy Ashton, the makeup designers of Hammer. I guess since the Hammer films are much more popular over in England than they are here in America and are probably seen by some as mostly knockoffs of the Universal movies, they and the people behind them don't get discussed as much. However, while the makeups and monster designs in the Hammer films aren't as iconic as those created by Jack Pierce, they're still rather striking and inventive and I think are worth discussion. Up first is Philip Leakey, whose first credit as makeup artist was on a 1949 film called The Adventures of P.C. 49: Investigating the Case of the Guardian Angel, which was not too long after he joined Hammer after having worked at Shepperton Studios for some time (according to IMDB trivia, his first make-up room at Hammer's Bray Studios was a converted toilet). From then to the mid-50's, he worked on many, many films as a typical makeup artist until 1955, when he worked on Hammer's first major foray into science fiction and horror: The Quatermass Xperiment. Leaky employed the use of a cast of an arthritic hand, latex, rubber, sponge-rubber, and plastic tubes to create the look of a rapidly mutating astronaut who, behind the end of the film, is completely transformed into a hideous mass of tentacles. He also worked closely with the film's cinematographer in order to light the actor during the early scenes of his mutation in an way that made him look gaunt and pitiful, as well as applying a mixture of liquid-rubber and glycerin to his skin to him look like he was sweating profusely. There are shots in the film of the mutating man's victims reduced to drained, shriveled corpses, effects that were also created by Leakey. The following year, Leakey worked on the makeup effects for X the Unknown, another sci-fi/horror film about a hideous monster on the rampage, this time in Scotland. Unfortunately, I've never seen the film myself so I can't comment on the quality of the makeup but I'm aware that this film is significant in that it was the first film to credit someone, namely Leakey, for "special makeup effects." It undoubtedly must have some power to it then.

Going back to makeup for a bit, I feel like I must give credit to a couple of guys whom I've never heard mentioned or discussed in any major way save for a couple of fleeting acknowledgements. I'm talking Philip Leakey and Roy Ashton, the makeup designers of Hammer. I guess since the Hammer films are much more popular over in England than they are here in America and are probably seen by some as mostly knockoffs of the Universal movies, they and the people behind them don't get discussed as much. However, while the makeups and monster designs in the Hammer films aren't as iconic as those created by Jack Pierce, they're still rather striking and inventive and I think are worth discussion. Up first is Philip Leakey, whose first credit as makeup artist was on a 1949 film called The Adventures of P.C. 49: Investigating the Case of the Guardian Angel, which was not too long after he joined Hammer after having worked at Shepperton Studios for some time (according to IMDB trivia, his first make-up room at Hammer's Bray Studios was a converted toilet). From then to the mid-50's, he worked on many, many films as a typical makeup artist until 1955, when he worked on Hammer's first major foray into science fiction and horror: The Quatermass Xperiment. Leaky employed the use of a cast of an arthritic hand, latex, rubber, sponge-rubber, and plastic tubes to create the look of a rapidly mutating astronaut who, behind the end of the film, is completely transformed into a hideous mass of tentacles. He also worked closely with the film's cinematographer in order to light the actor during the early scenes of his mutation in an way that made him look gaunt and pitiful, as well as applying a mixture of liquid-rubber and glycerin to his skin to him look like he was sweating profusely. There are shots in the film of the mutating man's victims reduced to drained, shriveled corpses, effects that were also created by Leakey. The following year, Leakey worked on the makeup effects for X the Unknown, another sci-fi/horror film about a hideous monster on the rampage, this time in Scotland. Unfortunately, I've never seen the film myself so I can't comment on the quality of the makeup but I'm aware that this film is significant in that it was the first film to credit someone, namely Leakey, for "special makeup effects." It undoubtedly must have some power to it then.  His next gig was The Curse of Frankenstein, the film that started off Hammer's legendary run of Gothic horror films. For the movie, Leakey was faced with the task of creating a Frankenstein monster that was memorable and striking without copying the iconic design by Jack Pierce. Ironically, though, when the original attempt to create the makeup design from a cast of Christopher Lee's head didn't work out, Leakey had to make it with simple, household materials like cotton and such, similar to the "out of the kit" makeups that Pierce specialized in. He also came up with the final design the day before shooting, applying it directly to Lee's face, so it truly was a last minute thing, and since it wasn't made from a mold, it had to be built from scratch every day. It paid off, though. Lee may have hated being in the makeup and not having any lines but the look of the monster in that film is definitely one of the most memorable things about it (in truth, it's the only memorable thing about this particular Frankenstein monster at all but that's a critique for another day). After that, Leakey worked on Quatermass 2, The Abominable Snowman, Cat Girl, Horror of Dracula, and The Revenge of Frankenstein, the first sequel to Curse. The latter, which had him create more gruesome makeup effects and a new Frankenstein monster (albeit one not as striking as the one played by Lee), proved to be his last film for Hammer as he became frustrated when the studio's cost-cutting measures led to his retainer being cut. After he left the studio, he continued working as a makeup man up until 1975 when he retired but he never worked on any films that were as memorable as those he did at Hammer. Leakey died in 1992 at the age of 84.

His next gig was The Curse of Frankenstein, the film that started off Hammer's legendary run of Gothic horror films. For the movie, Leakey was faced with the task of creating a Frankenstein monster that was memorable and striking without copying the iconic design by Jack Pierce. Ironically, though, when the original attempt to create the makeup design from a cast of Christopher Lee's head didn't work out, Leakey had to make it with simple, household materials like cotton and such, similar to the "out of the kit" makeups that Pierce specialized in. He also came up with the final design the day before shooting, applying it directly to Lee's face, so it truly was a last minute thing, and since it wasn't made from a mold, it had to be built from scratch every day. It paid off, though. Lee may have hated being in the makeup and not having any lines but the look of the monster in that film is definitely one of the most memorable things about it (in truth, it's the only memorable thing about this particular Frankenstein monster at all but that's a critique for another day). After that, Leakey worked on Quatermass 2, The Abominable Snowman, Cat Girl, Horror of Dracula, and The Revenge of Frankenstein, the first sequel to Curse. The latter, which had him create more gruesome makeup effects and a new Frankenstein monster (albeit one not as striking as the one played by Lee), proved to be his last film for Hammer as he became frustrated when the studio's cost-cutting measures led to his retainer being cut. After he left the studio, he continued working as a makeup man up until 1975 when he retired but he never worked on any films that were as memorable as those he did at Hammer. Leakey died in 1992 at the age of 84.