When I think back to when I was a little kid who loved the classic Universal monsters, I remember the ones I initially gravitated to the most were the Frankenstein monster, the Wolf Man, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon, aka the Gill Man. But when it came to Dracula, it took me a while to get into him, as I didn't have as much of an immediate, concrete visual to grasp onto. While I knew of those other monsters from images in books and catching snippets of various films on television, I think my first concrete image of Dracula was from an early 90's commercial I've mentioned before, which had the Frankenstein monster bringing some Doritos and drinks to a Halloween party, where Dracula is among the guests. I can still remember him saying, "No dip?", and the poor monster groaning before having to go back out to look for it. My mom, who saw the commercial as well, told me who Dracula was, but it didn't register in my young brain of only four or five, neither did the concept of what a vampire was. But it didn't take long before I figured it out, thanks to library books I found (not the Dracula Crestwood House book but some that were more modern) and, weirdly enough, tapes for my 2-XL toy robot (which I still have). That was where I learned about the accepted lore of vampires, as well as of the real historical figure of Vlad the Impaler, minus the really gruesome details. There was even one tape where 2-XL actually interviewed Dracula himself! Soon, Dracula become another of the classic monsters I really liked, as I dressed up as him one Halloween and got a moving model of him as a decoration, along with others of Frankenstein's monster and the Wolf Man. But, like a lot of these monsters, I wouldn't actually see the original movie from 1931 until the weekend before Halloween in 1998, when I was 11 and it aired on Turner Classic Movies. That Saturday, I saw Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and The Wolf Man, while Dracula was on the next day. I didn't get to see the whole movie during that first sitting, and I don't think saw it right from the beginning, but I do know that I did start at some point during Renfield's journey to Castle Dracula. I can remember watching it and being quite captivated by things like the eerie, foggy settings, Dracula's dark, crumbling castle, the absence of a music score, Bela Lugosi's amazing performance, and such. I wouldn't see the film in its entirety for a few years but it, along with the other Universal Horrors I saw then, left quite an impression.

But, to be honest, over the years, Dracula has slipped down my personal ranking of the major Universal Horrors. While I certainly like it more than The Mummy, as well as maybe Lon Chaney's The Phantom of the Opera, I enjoy Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, The Wolf Man, and Creature from the Black Lagoon much, much more. I certainly respect it, and its place in horror history is inarguable, as both it and Frankenstein are major turning points, kick-starting the horror boom of

the 1930's and, in many ways, inventing the horror film as we still know

it today. Plus, like with Boris Karloff and the Monster, the film and Bela Lugosi created the definitive and most lasting cultural image of Count Dracula, one that none of the

other countless adaptations have touched. Along with Nosferatu and the first of the Hammer films in 1958, Dracula '31 is arguably the most important vampire movie of all time. But that doesn't change the fact that it is quite flawed, with the second and third acts not working as well as the first in Transylvania, and there's a feeling of visual flatness and sluggishness during the latter parts, moments in the story that are never tied up, and supporting characters who can't measure up to Dracula himself or some of the other, more interesting members of the cast. It's still a classic, to be sure, but it's a rough jewel of a film, and isn't my favorite Dracula movie besides (that's Hammer's Dracula, or Horror of Dracula).

|

| Carl Laemmle Jr. |

It's been suggested that Universal's hiring of Tod Browning to direct Dracula was meant as a way to entice Lon Chaney to take the role, since the two of them had made ten movies together and had enjoyed great financial success. Browning, in turn, may have already had Bela Lugosi in mind, as he'd recently worked with him in his first sound film, the 1929 mystery, The Thirteenth Chair. Plus, in an interview with the Los Angeles Examiner in July of 1930, Browning said of the role of Dracula, "I favor getting a stranger from Europe." Whatever the case, Browning is said to have been interested in the story of Dracula a long time before he made it, which isn't surprising, considering his lifelong interest in the macabre. But his direction of the film has often been criticized as being on the clunky side, coming off as static, slow, and even dull at certain points. Various reasons have been given for this, some citing Browning's inexperience in working with sound, others saying it was due to budget problems and studio interference (they did cut the movie without his input), and some have attributed it to his own personal problems, be it his alcoholism or depression over Chaney's death. Some of the actors described Browning as "disengaged," with one, David Manners, describing the production as completely disorganized, in general, and noting that he barely remembered Browning even being on the set. Regardless of whatever issues occurred during filming, Dracula was Browning's most financially successful movie, as well as his most well-known to this day. But it also marks the beginning of the end of his career, as he would only direct six more movies afterward.

Bela Lugosi is so iconic as Dracula that it's amazing to think his casting in the film was a virtual last minute decision, despite his having made the Broadway play a major success. It was only after Lon Chaney died and their other choices for the role fell through that Universal acquiesced and went with him. What's equally baffling to me is how, when writing about the movie in 101 Horror Movies You Must See Before You Die, Steven Katz, who wrote the screenplay for Shadow of the Vampire, panned Lugosi's performance. He went as far as to call Lugosi's enduring popularity, "Difficult to defend," referring to him as "dough-faced" and commenting, "There's not much to recommend his hammy, stylized performance." Um, are you high? He's entitled to his opinion but, man, that blows my mind. Not only is Lugosi's performance still considered one of the best things about this movie but his performance, while definitely theatrical, isn't what I'd call hammy (if you want hammy, watch Carlos Villarias in the Spanish version). In fact, while his gestures can come off as melodramatic, and his voice and speech pattern have been parodied to death (though, it's so iconic that I don't know how you can't love it), he is effectively creepy in the many scenes where he has no dialogue and uses his piercing eyes, blank face, and body language to get across Dracula's predatory nature. And a predator is very much how he comes off when he gnarls his long, talon-like fingers, spreads his cape, his elbows and shoulders making it look like a pair of wings, and slowly goes in for the bite. Also, his incredible pair of eyes give no doubt as to the hypnotic powers he has over others, be they his prey or his servants, whom he can also communicate with telepathically. The best example of this is when Dracula appears outside Renfield's cell and, without saying anything, orders him to do something that horrifies him, something that involves Mina. Renfield's pleading with him and Dracula's cruel expression and piercing eyes say everything perfectly.

As iconic and eternal as Lugosi's performance is, though, his Dracula is hardly a complex character, in that he is just purely evil to the core. Those moments where he's a charming, gracious host to Renfield at his

castle and a romantic, fascinating stranger to those he meets in high

London society are nothing more than a facade for the parasitic, undead

ghoul he truly is. Other than the scene in the concert hall, where he laments his existence to the unsuspecting Jonathan Harker, Mina, and Lucy Weston, intoning, "To die. To be really dead. That

must be glorious... There are far worse things awaiting man than death," there is absolutely no hesitation or remorse over the horrible things he does because he has no choice. In fact, while he's fairly stoic for the most part, there are moments where he does seem to take pleasure in what he does, such as the opportunistic manner in which he preys on the flower girl and the evil sneer he has when he bites Mina for the first time. Having left Transylvania behind to seek out new victims in a fresh and defenseless country, Dracula doesn't stop at merely drinking their blood for sustenance. He also makes Renfield his mad, insect-eating slave, turns Lucy into a vampire who, horrifically, preys on young children, and then sets his sights on Mina, planning to make her his new vampire bride, going as far as to make her drink his own blood. He virtually boasts about this to Prof. Van Helsing, telling him, "You are too late. My blood now flows through her veins. She will live through the centuries to come, as I have lived." And when Van Helsing counters by saying they know how to save Mina, Dracula retorts, "If she dies by day. But I shall see that she dies by night." Speaking of Van Helsing, Dracula, who already knows of him before he meets him, realizes what a formidable enemy he is when he shows him the mirror in the cigarette box, prompting the Count to lose his composure and smack it out of his hands. He glares at Van Helsing for a few seconds, then relaxes, excuses himself to both Harker and Dr. Seward, and leaves, telling them that Van Helsing will explain his reaction. Before he does leave, he can't help but admire the professor's cleverness, saying, "For one who has not lived even a single lifetime, you are a wise man, Van Helsing."

must be glorious... There are far worse things awaiting man than death," there is absolutely no hesitation or remorse over the horrible things he does because he has no choice. In fact, while he's fairly stoic for the most part, there are moments where he does seem to take pleasure in what he does, such as the opportunistic manner in which he preys on the flower girl and the evil sneer he has when he bites Mina for the first time. Having left Transylvania behind to seek out new victims in a fresh and defenseless country, Dracula doesn't stop at merely drinking their blood for sustenance. He also makes Renfield his mad, insect-eating slave, turns Lucy into a vampire who, horrifically, preys on young children, and then sets his sights on Mina, planning to make her his new vampire bride, going as far as to make her drink his own blood. He virtually boasts about this to Prof. Van Helsing, telling him, "You are too late. My blood now flows through her veins. She will live through the centuries to come, as I have lived." And when Van Helsing counters by saying they know how to save Mina, Dracula retorts, "If she dies by day. But I shall see that she dies by night." Speaking of Van Helsing, Dracula, who already knows of him before he meets him, realizes what a formidable enemy he is when he shows him the mirror in the cigarette box, prompting the Count to lose his composure and smack it out of his hands. He glares at Van Helsing for a few seconds, then relaxes, excuses himself to both Harker and Dr. Seward, and leaves, telling them that Van Helsing will explain his reaction. Before he does leave, he can't help but admire the professor's cleverness, saying, "For one who has not lived even a single lifetime, you are a wise man, Van Helsing."

As for Renfield, when Dracula overhears him telling Van Helsing and the others about the moment he became his slave, he doesn't take this betrayal lightly. And when Harker and Van Helsing show up at Carfax Abbey, having followed Renfield there, Dracula, convinced that he purposefully led them there, cruelly kills Renfield, cursing him to eternal damnation due to all the innocent blood on his hands. However, it's right then when Dracula ends up getting himself killed by stupidly running into the room housing his

coffin with Mina and slips inside it, leaving him open to being staked. Even though day was breaking at that moment, it was so dark in there, with no apparent ways for the sunlight to shine in, that he could've easily hid from them with Mina and even taken them out when the opportunity arose. Mina says that he wasn't able to completely turn her into a vampire because, "The daylight stopped him," although, again, I don't see how that was possible at all.

coffin with Mina and slips inside it, leaving him open to being staked. Even though day was breaking at that moment, it was so dark in there, with no apparent ways for the sunlight to shine in, that he could've easily hid from them with Mina and even taken them out when the opportunity arose. Mina says that he wasn't able to completely turn her into a vampire because, "The daylight stopped him," although, again, I don't see how that was possible at all.

It's been said many times ad nauseam, including by myself, but it can't be emphasized enough how much Dracula's portrayal here is the stereotypical, popular image of the Count. Not only is it Bela Lugosi's voice but also his handsome features, which the literary Dracula never had, and his iconic costume, with the flowing black cape (the inside of which is red, though you wouldn't know it), the wing-like collar, the tuxedo underneath, the star-shaped amulet he wears around his neck, and the ring on his left hand. As for his actual look,

Jack Pierce, who was now the head of Universal's makeup department, came up with a light-green greasepaint that, on black-and-white film, would make him appear deathly pale. However, Lugosi offended Pierce when he insisted on applying the makeup himself, which he'd done onstage, like all theater actors up to that point, and there were not yet union rules keeping him from doing so on the movie. Also, while Lugosi's Dracula is often depicted with a widow's peak, that was only for promotional material; as you can see in the

screenshots, he doesn't have them in the actual movie, nor does he ever have fangs (in fact, it wouldn't be until the 1950's that movie vampires, in general, did have fangs). And cinematographer Karl Freund famously emphasized Dracula's hypnotic gaze by focusing light on his eyes in numerous shots. Besides the very image, a lot of the popular vampire tropes also come from this movie. While Nosferatu was the first to establish the idea that exposure to sunlight destroys vampires, this film, like in the novel, firmly established the notion of vampires having to sleep in a coffin lined with their native soil, as well as that they cast no reflection, they're repelled by religious symbols, and can be killed by driving a stake through their hearts. And though they mostly happen offscreen, Dracula has many of his traditional abilities, like being able to turn into a bat, as well as a wolf, and he can also pass through things went it suits him, like the enormous spiderweb in his castle. The only outlier is the use of wolfsbane to repel vampires, instead of the traditional garlic.

Jack Pierce, who was now the head of Universal's makeup department, came up with a light-green greasepaint that, on black-and-white film, would make him appear deathly pale. However, Lugosi offended Pierce when he insisted on applying the makeup himself, which he'd done onstage, like all theater actors up to that point, and there were not yet union rules keeping him from doing so on the movie. Also, while Lugosi's Dracula is often depicted with a widow's peak, that was only for promotional material; as you can see in the

screenshots, he doesn't have them in the actual movie, nor does he ever have fangs (in fact, it wouldn't be until the 1950's that movie vampires, in general, did have fangs). And cinematographer Karl Freund famously emphasized Dracula's hypnotic gaze by focusing light on his eyes in numerous shots. Besides the very image, a lot of the popular vampire tropes also come from this movie. While Nosferatu was the first to establish the idea that exposure to sunlight destroys vampires, this film, like in the novel, firmly established the notion of vampires having to sleep in a coffin lined with their native soil, as well as that they cast no reflection, they're repelled by religious symbols, and can be killed by driving a stake through their hearts. And though they mostly happen offscreen, Dracula has many of his traditional abilities, like being able to turn into a bat, as well as a wolf, and he can also pass through things went it suits him, like the enormous spiderweb in his castle. The only outlier is the use of wolfsbane to repel vampires, instead of the traditional garlic.

Though they have no role other than to be creepy and briefly stalk Renfield, Dracula's three brides (Geraldine Dvorak, Cornelia Thaw, and Dorothy Tree) are still memorable as these pale but very lovely vampire women you see rise from their coffins along with Dracula, one of whom you even see before the Count. Also, like some other parts of the story, nothing more is made of them once Dracula heads to England, meaning they're likely still haunting Castle Dracula and preying on the nearby villagers, even after Dracula himself is killed at the end. And unlike with Bela Lugosi, Jack Pierce was able to actually apply the makeup to the brides.

Unfortunately, Bela Lugosi is so awesome that some of the other actors pale in comparison. I just now realized that I've made this same statement before, like when talking about Max Schreck's performance as Count Orlok in Nosferatu and Lon Chaney's performance in The Phantom of the Opera, as well as others I've probably forgotten, but it is also true about Dracula, though not as severely. Just like with those two movies, the weakest characters are the two young, romantic leads: Jonathan Harker (David Manners) and Mina Seward (Helen Chandler). Manners had a run of pretty bad luck in Universal horror films, often playing bland and ineffectual romantic leads who were totally overshadowed by the villains he went up against. Even though Jonathan Harker is, to this day, the role for which he's most remembered (something he never understood or cared for, as he claimed to have never even seen the movie and had no desire to), because they gave Harker's role in the book to Renfield, he

doesn't have much to do. His performance consists of mainly worrying about Mina's deteriorating health, his initial disbelief that Dracula is a vampire and is preying on her, arguing and battling with Van Helsing over the ill effects he believes his methods are having on her, trying to take her away to London, and, during the final scene, futilely searching for Mina, while Van Helsing is the one who stakes Dracula. Also, consider this: Manners' salary was four times that of Lugosi's.

Though I don't think Helen Chandler was that compelling of an actor, Mina is a little more interesting than Harker, as she's the one who's being seduced and corrupted by Dracula and, eventually, begins to become a vampire as well. That latter section of the movie is where Chandler's acting truly shines. Not only does she grow to despises the scent of wolfsbane and the sight of a cross, she also talks about loving the night and, before attempting to attack Harker, she tries to manipulate him into getting rid of Van Helsing's crucifix, similar to how Dracula had been hypnotizing the nurse, Briggs, to interfere with the professor's attempts to save Mina. And when Van Helsing stops her with a cross, Mina tearfully describes to Harker how Dracula forced her to drink his own blood from a vein in his arm. Similarly, her description of her first nighttime visit from Dracula as a horrific nightmare, and when she later sees Lucy Weston after she's become a vampire, are well-acted and rather creepy in her telling of them. But, other than that, Mina doesn't leave much of an impression, often coming across as either bland or melodramatic, and in the end, she's a catatonic damsel in distress who needs to be rescued before Dracula can fully corrupt her.

Mina's friend, Lucy Weston (Frances Dade), is a character whom I find to be a little more memorable than Mina herself. When Dracula first meets her, Harker, Mina, and Dr. Seward at the Royal Albert Hall, Lucy proves to have an interest in the macabre, saying that Carfax Abbey makes her think of a toast that goes, "Lofty timbers, the walls around are bare, echoing to our laughter, as though the dead were there." She tries to say more, adding, "Quaff a cup to the dead already, hurrah for the next to die!", but Mina stops her. It's implied that this may be why Dracula goes after her first. Moreover, when Mina spends the night with Lucy, she says she finds Dracula to be interesting and exotic, while Mina just thinks he's kind of weird. Lucy then daydreams about his castle in Transylvania, while Mina jokingly tells her, "Well, Countess! I'll leave you to your Count and his ruined abbey!" Those words prove to be prophetic, as Dracula enters Lucy's room after she goes to bed and kills her, causing her to later rise as a vampire herself. She then goes on an

off-screen rampage, attacking children at night, which makes the papers, and Mina tells Van

Helsing that she encountered her in the night and was horrified by

the savage, animalistic look on her face. Van Helsing promises Mina that he will save Lucy's soul... and we never hear

anything more about it. Is Lucy still prowling the

streets of London or did she die when Dracula was killed? This is another of the story-points that are never resolved.

Besides Dracula himself, the most memorable character is Renfield, played by the amazing and woefully underrated Dwight Frye. At the beginning of the movie, he appears to be the protagonist: a well-dressed, mannered, if naive,

gentleman who's come to Transylvania on a business matter and simply has to go through with his job, regardless of the fears and superstitions of the locals. Despite the innkeeper's warning about Count Dracula being a vampire, Renfield, after accepting a crucifix from his wife, heads on to Borgo Pass to meet Dracula's coach. Though he's obviously spooked by the eerie countryside, the unsettling coach driver (whom he, somehow, can't tell was Dracula when he meets him formally), and getting dumped off at a seemingly empty, rundown castle, he's relieved when he meets the Count and is shown to a room. Though there are things about Dracula that he finds unnerving, particularly his stare, and the eerie atmosphere outside does kind of get to him, he's comfortable enough to close the sale of Carfax Abbey with him and prepare to bed down for the night. But Renfield passes out from the drugged wine he was given and Dracula, after sending away his three brides when they attempt to close in on him, bites and feeds on Renfield himself.

As Dracula's slave, Renfield is the antithesis of who he was before: a wide-eyed, raving

madman who loves eating insects and spiders. While Dracula is able to freely roam London, searching for victims, Renfield is confined to the Seward Sanatorium, but nothing can constrain his manic performance, as his crazed eyes, creepy

laugh, and bizarre movements and expressions keep you on edge, never

knowing when he's about to snap. He often escapes from his cell and tends to eavesdrop on the other characters' conversations, often not even trying to hide himself. However, Renfield also proves to be the film's most complex character, as he's often conflicted about whose side he's on. While he always refers to Dracula as "Master" and insists that he's loyal, there are

times where he tries to warn others of him. He's particularly

concerned about Mina, asking Dr. Seward to send him away because he fears his cries in the night may cause her to have bad dreams, and futilely begs Dracula not to corrupt her. He even goes as far as to tell Seward and the others to listen to Van Helsing, but then, when he sees Dracula's bat form fluttering outside, he immediately backpedals, telling him that he wasn't going to talk. Naturally, this arouses Van Helsing's suspicions, but Renfield claims not to know anything about Dracula. When Van

Helsing warns him that his soul will be damned if he dies with innocent

blood on his conscience, Renfield answers, "Oh, no. God will not damn one lunatic's soul. He knows that the powers of evil are too great for those of us with weak minds." But that proves to be false confidence on his part. At the end, when he realizes Dracula is going to kill

him, he pleads for his life, exclaiming that he will be eternally punished if he dies with all those lives on his conscience.

Though his entire performance is a bravura one for sure, my personal favorite scene with Renfield is when he tells Van Helsing exactly what happened when he became Dracula's slave. "He came and stood below my window in the moonlight. And he promised me things, not in words, but by doing them... By making them happen. A red mist spread over the lawn, coming on like a

flame of fire! And then he parted it. And I could see that there were

thousands of rats, with their eyes blazing red! Like his, only smaller. And then he held up his hand, and they all stopped, and I thought he seemed

to be saying: 'Rats! Rats! Rats! Thousands! Millions of them! All red

blood! All these will I give you... if you will obey me." Van Helsing then asks, "What did he want you to do?", and Renfield answers, "That which has already been done," before chuckling in that creepy manner of his. Unbeknownst to him, Dracula was standing outside, watching and listening, and so, when Renfield meets with him at Carfax Abbey during the final scene, only for Jonathan Harker and Van Helsing to then show up, Dracula thinks he's committed the ultimate betrayal and led them to him. Sadly, Renfield's pleading for his life falls on deaf ears and Dracula sends him tumbling down the staircase to his death.

There are a few things I've never understood about Renfield. Even though he can apparently walk around in daylight

and only craves insect, spiders, and the like, Van Helsing mentions how he continually escapes from his cell, going off to do God knows what. In a similar vein, there's a moment where it seems like he's about to bite the neck of a maid who fainted at the sight of him, though the scene then cuts and we never learn what happened. It's also implied that there's something unusual about his blood, and according to Martin,

his caretaker, he can bend his cell's bars in order to escape which, despite how strong a lunatic can be, seems like quite a feat. So, even if he's not a full-on vampire, is Renfield still even human now? Plus, what use is he to Dracula, really? Not only is he locked up in the sanatorium for the duration of the second and third acts, but all he really does is hinder him by telling Van Helsing and the others everything there is to know. In fact, now that I think about it, most versions of the character are pretty superfluous to the plot, making me wonder if there's any point in even including him in the story (though, in this case, I'm glad they did).

his caretaker, he can bend his cell's bars in order to escape which, despite how strong a lunatic can be, seems like quite a feat. So, even if he's not a full-on vampire, is Renfield still even human now? Plus, what use is he to Dracula, really? Not only is he locked up in the sanatorium for the duration of the second and third acts, but all he really does is hinder him by telling Van Helsing and the others everything there is to know. In fact, now that I think about it, most versions of the character are pretty superfluous to the plot, making me wonder if there's any point in even including him in the story (though, in this case, I'm glad they did).

While Peter Cushing will always be the definitive Van Helsing in my book, Edward Van Sloan is probably a close second, as he brings a major

sense of gravitas to the role, with a deep air of respectability and

kindliness. He first appears when he's called in to examine Renfield's blood, and after doing so, he determines that a vampire is behind both Renfield's madness and the recent death of Lucy Weston. Naturally, Dr. Seward and the others don't believe what he says, but Van Helsing remains confident in his theory and slowly gathers evidence, such as Renfield's violent reaction to some wolfsbane and Mina's having the tell-tale bite marks on her neck ever since she had a horrible "nightmare." Immediately after he's introduced to Count Dracula, he realizes he's the vampire in question when he sees he has no reflection in a small mirror in a cigarette box. He's then clever enough to make Dracula out himself when he opens the box in front of him and he reacts by smacking it to the floor. Though the others are still skeptical, initially, when Mina is found out on the lawn after being attacked by Dracula, and there are reports of Lucy, now a vampire herself, attacking children at night, they come over to his side. Besides being a sometimes stern authority figure, insisting that everyone listen to what he says, Van Helsing also has a

very kind, nurturing side to him, coming across like a sweet old grandfather in how he comforts Mina about what's happening to her, as well as her horror over what Lucy has become. He even does the same for Jonathan Harker at one point, explaining to him why it would do no good to simply take Mina away, and that they can only save her by destroying Dracula. And when he realizes Renfield is connected to Dracula in some manner, he's able to work him in order to make him talk, sincerely warning him of his impending damnation if he dies with innocent blood on his hands.

Van Helsing's best scene is his standoff with Dracula, where

he proves just how much of a worthy foe he is for the Count. He not only tells him that he knows how to save Mina's soul and life, but when Dracula says that he will make sure she dies by night, Van Helsing retorts, "And I will have Carfax Abbey torn down, stone by stone, excavated a mile

around. I will find your earth-box, and drive that stake through your

heart." Even more awesome than that, he proves to have a will strong enough to resist

Dracula's hypnotic power, and when the Count lunges at him, he calmly pulls out a crucifix and drives him away. He later uses the crucifix to stop Mina from biting Harker's neck, and when Martin is caught shooting at the "big, gray bat" that's been flying around, Van Helsing tells him, "There's no use of wasting your bullets, Martin. They cannot harm that bat." And, of course, during the finale, Van Helsing is the one who stakes Dracula, putting an end to his reign of terror.

There's little to say about Dr. Seward (Herbert Bunston) other than, as the director of the sanatorium, he's a fairly kind authority figure, albeit stern when he has to be whenever Renfield acts out. Like the others, he's initially skeptical of Van Helsing's theory about there being a vampire prowling London, let alone that it's Count Dracula, but when his daughter falls under Dracula's influence, Seward turns around and begins listening to what Van Helsing says. One minor character who I particularly

like is Martin (Charles Gerrard), the man charged with looking after

Renfield. He's a very obvious comic relief character, with his thick Cockney

accent (I especially like the way he

says "beautiful" and "crazy), stark white uniform, and rather silly, mustached face, but he does it really well. Even though he has to keep a

constant eye on Renfield, whom he calls "old fly eater," putting him back in his cell after every time he escapes, he doesn't seem that irritated about it. In fact, he seems to find Renfield kind of amusing, given how he sounds like he's stifling a laugh when describing how he howls at the wolves at night, and there even moments where appears to have some affection for him. Like just about everyone else, Martin doesn't believe in the existence of vampires, even after reading about Lucy's attacks on young girls in the paper. That said, when he eavesdrops on Renfield's description of the moment he became Dracula's servant, he admits that he had him going, especially after he saw how Renfield bent his cell's bars. However, his last

scene is really odd. After trying to shoot Dracula's bat form, Van

Helsing tells him not to waste his bullets. A maid says to Martin that Van Helsing is

crazy, to which Martin retorts, "They're all crazy. They're all crazy, except you and me. Sometimes I have me doubts about you." To that, she

just says, "Yes." Martin then looks at her very seriously and slowly

backs away from her, into the dark, never taking his eyes off her. To this day, I find that moment to be really weird. I'm sure Martin's reaction is meant to be him a little freaked out by her admitting that she also doubts her own sanity, but it's played off in such a quirky and random manner.

A couple of other minor characters worth noting include the young woman who's riding in the coach with Renfield at the beginning of the movie, reading in a book, "Among the rugged peaks that frown down upon the Borgo Pass are found crumbling castles of a bygone age." Though the character herself is insignificant, what is significant is that she's played by Carla Laemmle', Carl Laemmle's niece, and she had the distinction of speaking the first lines in the first sound, supernatural horror film made in America. She appeared as an extra in a number of small parts in films of the 20's and 30's, including as one of the ballerinas in The Phantom of the Opera. There's also the Transylvanian innkeeper (Michael Visaroff) who tries to warn Renfield not to go to Castle Dracula, telling him, in a very melodramatic manner, of the vampires and their nature. Similarly, the innkeeper's wife (Barbara Bozoky), upon seeing that Renfield is insistent upon going, gives him a crucifix, which she asks him to wear, "For your mother's sake." The crucifix does, unbeknownst to him, initially protect him from Dracula, but, naturally, it only works for so long.

While the movie does have its fair share of flaws, which I'll get into shortly, most agree that the first act in Transylvania is where it's at its strongest, as do I. Right from the opening, as the coach speeds through the countryside, there's a sense of dread in the air, as one of the passengers tells Renfield, when he asks the driver to slow down, that they must reach the inn before nightfall. He says it's "Walpurgis Night," a night of evil, and tells a woman sitting in the coach as well, "On this night, madam, the doors, they are barred. And to the Virgin, we pray," as he and his wife cross themselves. Then, when they reach the inn, the innkeeper, coachman, and others are shocked when Renfield says he's going on to Borgo Pass. The innkeeper tries to make him wait until the next morning, only to learn that he's meeting Count Dracula's coach at midnight. He warns Renfield of the vampires and, pointing out the setting sun, tells him they must get inside. But Renfield is insistent

about heading on to the pass and, as he rides off, the others watch and speak prayers in despair, knowing that he's doomed. The movie's true creep factor comes in when we get the eerie scene in Castle Dracula's crypt, where the vampires slowly rise from their coffins and we see the Count himself for the first time. The lack of music and the very few sound effects you hear, chief among them the sound of a wolf howling outside, make the scene especially unnerving. Then, when Dracula meets Renfield at Borgo Pass, the scene, which is probably my favorite in the whole movie, is bathed in atmosphere. There's so much fog that it feels like something out of a nightmare, and when Renfield approaches Dracula, we get what I think is one of the scariest images in movie history: a close up of Dracula staring right at the camera, his piercing eyes glowing as mist swirls by him. It never feels to creep me out. And while some may laugh at the prop, I also think the moment where Renfield looks out the window and sees a bat fluttering above the horses is spooky as well.

about heading on to the pass and, as he rides off, the others watch and speak prayers in despair, knowing that he's doomed. The movie's true creep factor comes in when we get the eerie scene in Castle Dracula's crypt, where the vampires slowly rise from their coffins and we see the Count himself for the first time. The lack of music and the very few sound effects you hear, chief among them the sound of a wolf howling outside, make the scene especially unnerving. Then, when Dracula meets Renfield at Borgo Pass, the scene, which is probably my favorite in the whole movie, is bathed in atmosphere. There's so much fog that it feels like something out of a nightmare, and when Renfield approaches Dracula, we get what I think is one of the scariest images in movie history: a close up of Dracula staring right at the camera, his piercing eyes glowing as mist swirls by him. It never feels to creep me out. And while some may laugh at the prop, I also think the moment where Renfield looks out the window and sees a bat fluttering above the horses is spooky as well.

The atmosphere continues when Renfield arrives at the castle, finds that the coachman has disappeared, and slowly makes his way inside when the creaking door slowly opens by itself. Inside, we have the legendary moment where Dracula descends the stairs with a candle, introduces himself to Renfield, and as the two of them head upstairs, Renfield is startled by the sound of wolves. Dracula, though, finds them delightful, intoning his classic line, "Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make." And when Renfield has to hack his way through an enormous spiderweb in the middle of the staircase and spots the large spider crawling away, Dracula comments, "The spider spinning his web for the unwary fly. The blood is the life, Mr. Renfield." Up in his guest room, Renfield closes the deal with Dracula, while the Count peers at him with those eyes of his. Then, in a moment that was inspired by Nosferatu, which Universal had acquired a print of, Renfield cuts his finger on a paperclip, arousing Dracula's bloodlust. Unbeknownst to him, the crucifix that the innkeeper's wife gave him repels the vampire. That's when Dracula gives him some wine, which he says is very old, and when Renfield asks him if he's going to partake in it as well, we get another popular line: "I never drink... wine." After Dracula leaves him for the night, Renfield, feeling the effects of the drug, walks over to a window, and opens it up, unaware that he's being stalked by Dracula's brides. He faints at the sight of a bat, and the vampires slowly move in on him, only for Dracula to appear out of the thick fog and send them back. He then preys on Renfield himself, albeit offscreen.

Before we go on, I have to comment on how everything we now see as a cliche concerning vampire movies and Gothic horror, in general, comes from this first act of Dracula. Besides the already mentioned common tropes revolving around vampires themselves, you have the superstitious villagers, the crypt where the vampires sleep in their coffins, the eerie, fog-riddled countryside, and, most famously of all, the old, rundown castle, full of cobwebs, bats hovering outside, the long, winding

staircase, and the ever-present thick fog outside. While much of this was likely taken from German Expressionism, it's now become such an expected part of the genre through pop-culture osmosis that its actual origins have long since been forgotten. Granted, as many have pointed out, I don't know why there are armadillos and Jerusalem crickets, neither of which are from Transylvania, roaming around, but at the same time, the fact that they are so out of place kind of helps the castle feel otherworldly and off-putting.

Though there's not much to say about the journey to London onboard the Vesta, that scene does have another memorable shot of Dracula's face, with his eyes spotlighted, as he listens to Renfield. He then goes up on deck and watches the ship's crew, as they feverishly attempt to navigate a violent storm (the footage of them is taken from a silent film, The Storm Breaker), unaware that they're about to become victim to something far worse. Once the Vesta arrives in England, we get just a little bit of

the aftermath of Dracula's rampage, including a memorably Expressionistic shadow of the captain, whose corpse is tied to the wheel, followed by the discovery of Renfield down in the hold. The shot of him at the bottom of the stairs leading down from the deck, laughing creepily as he looks up at the camera with his insane eyes, is quite creepy. In the fog-shrouded streets of London, we get the moment where Dracula preys on a flower girl, then nonchalantly walks among the populace, all

unaware of the monstrous creature he truly is, while the police find the girl's body. The scene with the flower girl is a bit of a prelude to what I think is the most effective moment in this part of the movie, when Dracula goes for Lucy Weston. He watches her from outside her apartment, as she opens her bedroom window to let in some fresh air, then gets in bed and grabs a book. Dracula hovers outside her window in bat form, and Lucy, either through simple drowsiness or, perhaps, by his influence (as suggested by the cutting back and

forth between them), falls asleep. Dracula then appears in the room and slowly creeps towards her, baring his claw-like fingers as he goes in for the bite. Again, it's absolutely silent, to the point where you could mute it and there would be very little difference, making it come off as almost dreamlike.

the aftermath of Dracula's rampage, including a memorably Expressionistic shadow of the captain, whose corpse is tied to the wheel, followed by the discovery of Renfield down in the hold. The shot of him at the bottom of the stairs leading down from the deck, laughing creepily as he looks up at the camera with his insane eyes, is quite creepy. In the fog-shrouded streets of London, we get the moment where Dracula preys on a flower girl, then nonchalantly walks among the populace, all

unaware of the monstrous creature he truly is, while the police find the girl's body. The scene with the flower girl is a bit of a prelude to what I think is the most effective moment in this part of the movie, when Dracula goes for Lucy Weston. He watches her from outside her apartment, as she opens her bedroom window to let in some fresh air, then gets in bed and grabs a book. Dracula hovers outside her window in bat form, and Lucy, either through simple drowsiness or, perhaps, by his influence (as suggested by the cutting back and

forth between them), falls asleep. Dracula then appears in the room and slowly creeps towards her, baring his claw-like fingers as he goes in for the bite. Again, it's absolutely silent, to the point where you could mute it and there would be very little difference, making it come off as almost dreamlike.

The fact that you don't ever see Dracula actually bite any of his victims leads us into one of the movie's most noteworthy aspects: its extreme subtlety. As Maitland McDonagh says when talking about it on Bravo's 100 Scariest Movie Moments, "You

see so little in Dracula, it's quite extraordinary." She then equates it to the movie being based more on the stage play than Bram Stoker's book, which could be true. However, I think money constraints and possible censorship problems may have also played a role, as you never see the actual bites themselves, either; instead, you have people remarking on them. (Though, I say that, then I remember the rather graphic close-ups of Renfield's bleeding finger after he cuts himself.) Others I think were just for practicality, like how the camera always pans away when Dracula emerges from his coffin, as watching him climb out might make him less scary. Also, as I mentioned, Dracula's transformations into his various forms happen offscreen, as he becomes a bat in-between shots (and, again, while some may laugh at the bat props, I think they work fine and, ironically, come off better than the fake bats you'd see in many later vampire movies). Moreover, while he's said to be able to become a wolf, you never actually see this form. You often

hear wolves howling, both in Transylvania and in London, hinting at his presence, but his wolf form is only alluded to. An example is when Renfield hears a wolf howl outside his cell and quietly

says, "Yes, master,"

then looks out the window to see Dracula standing in the yard below. The most blatant allusion, though, comes after Dracula smashes the mirror. He leaves by the balcony and Jonathan Harker follows, only to look outside and exclaim, "What's that? Running across the lawn? Looks like a huge dog!" Van Helsing then suggests that Dracula became a wolf once out of sight to keep them from following him. Other examples of subtlety include how, within a short cutaway, Dracula is suddenly on the other side of the big spider-web obstructing

the staircase in his castle without disturbing it; Dracula's offscreen rampage aboard the Vesta; how we never find out exactly what Renfield does during some of the times he's escaped from his room; Dracula's actual corruption of Mina, which, again, you never see (that would've been way too graphic to show; even during the Pre-Code era); and even Dracula's actual staking, as you only hear him yelling and grunting offscreen. Some feel that the latter is anticlimactic but, again, I'm more put off by how stupidly Dracula trapped himself in there; just hearing the pounding and him groaning as he's staked is more than enough.

then looks out the window to see Dracula standing in the yard below. The most blatant allusion, though, comes after Dracula smashes the mirror. He leaves by the balcony and Jonathan Harker follows, only to look outside and exclaim, "What's that? Running across the lawn? Looks like a huge dog!" Van Helsing then suggests that Dracula became a wolf once out of sight to keep them from following him. Other examples of subtlety include how, within a short cutaway, Dracula is suddenly on the other side of the big spider-web obstructing

the staircase in his castle without disturbing it; Dracula's offscreen rampage aboard the Vesta; how we never find out exactly what Renfield does during some of the times he's escaped from his room; Dracula's actual corruption of Mina, which, again, you never see (that would've been way too graphic to show; even during the Pre-Code era); and even Dracula's actual staking, as you only hear him yelling and grunting offscreen. Some feel that the latter is anticlimactic but, again, I'm more put off by how stupidly Dracula trapped himself in there; just hearing the pounding and him groaning as he's staked is more than enough.

For a movie that had to keep costs down, Dracula does have some scope to it, at least during the first half. It opens on an awesome matte painting of mountains in the background of the shot of the carriage rushing to the inn, and while the shots of the "village" consist of just some exteriors of the inn and the yard in front of it, it's much more wide open than what we get later on. The first shots we get of Castle Dracula are a combination of more well-done matte paintings of the road leading to it and a well-done model of the castle itself, and while we don't get much of Borgo Pass (which was actually Vasquez Rocks Natural Area Park), the mist, eerie lighting, and Bela Lugosi's creepy performance here make more than make up for it. Of course, the immediate interior of Castle Dracula itself is breathtaking, a sense of scope and size that I'm sure was added onto with more matte work, and, as I said before, is so classic in its depiction that you can't help but love it. The same goes for the creepy crypt where the vampires' coffins are kept, as well as the room Renfield is showed to, which is, as Dracula himself puts it, more inviting, but still large and Gothic in style, especially with the French window leading outside, where there's thick mist everywhere. The settings become smaller and more constrained as the film goes on, with much of it feeling like a stage play, as we'll get to presently, but when Dracula first arrives in England, we get the foggy streets of London, and the interiors of the Royal Albert Hall, which is actually the redressed Paris Opera House set. Though we see it only once, the grounds of the Seward Sanatorium are nicely spacious, and the interiors of Carfax Abbey feel very much like those of Castle Dracula (it was done on the same stage), complete with the grand staircase and the crypt-like area where Dracula keeps his coffin.

While the movie does start to weaken around the halfway point, there are still moments of atmospheric greatness, like the scene between Dracula and Renfield when the latter is in his cell; when Dracula first visits Mina in her bedroom and goes in for the bite; Mina's description of the "dream" she had several nights before; and the scene where a policeman passes by an establishment on his bicycle, stops when he hears a child drying, and we then see Lucy walk off into

the night. But, by this point, the movie does begin to feel very stagey and confined. Many feel that it's the switch from Transylvania to London in and of itself that causes Dracula's quality to drop but, for me, it's how about 95% of the second and third acts take place to the Seward household, specifically the drawing room and Mina's bedroom (with that ugly piece of cardboard on her bedside lamp; I never noticed that until James Rolfe did a whole video on it but, once you know about it, you can't not look at it). Because it was based primarily on a

stage play, it's expected that there would be a lot of dialogue scenes that take place in just a few rooms (even the blocking of the actors feels like that of a play), but after the awesome, grand first act in Transylvania and the memorable setting of Castle Dracula, this feels very constraining. We still great scenes, like those I've just mentioned, as well as others like Van Helsing's confrontation with Dracula and Renfield's confession of how he became Dracula's slave, but even with the best actors present, those scenes really get tiresome after a while and you wish for another setting, like maybe some more scenes at Carfax Abbey or on the streets of London.

the night. But, by this point, the movie does begin to feel very stagey and confined. Many feel that it's the switch from Transylvania to London in and of itself that causes Dracula's quality to drop but, for me, it's how about 95% of the second and third acts take place to the Seward household, specifically the drawing room and Mina's bedroom (with that ugly piece of cardboard on her bedside lamp; I never noticed that until James Rolfe did a whole video on it but, once you know about it, you can't not look at it). Because it was based primarily on a

stage play, it's expected that there would be a lot of dialogue scenes that take place in just a few rooms (even the blocking of the actors feels like that of a play), but after the awesome, grand first act in Transylvania and the memorable setting of Castle Dracula, this feels very constraining. We still great scenes, like those I've just mentioned, as well as others like Van Helsing's confrontation with Dracula and Renfield's confession of how he became Dracula's slave, but even with the best actors present, those scenes really get tiresome after a while and you wish for another setting, like maybe some more scenes at Carfax Abbey or on the streets of London.

Dracula definitely benefited from having the legendary Karl Freund as its cinematographer. Having started out in Germany, shooting movies such as The Golem, F.W. Murnau's The Last Laugh, and Fritz Lang's Metropolis, Freund brought his experience with German Expressionism to Hollywood movies such as this and the following year's Murders in the Rue Morgue, as well as the movies he directed like The Mummy and Mad Love. As I've already noted, the film's look is steeped in it, with all the shadows, fog, and instances of total darkness, with the characters sometimes in almost total silhouette. A good example is the scene near the end where Dracula takes control of Briggs and commands her to remove the wolfsbane from the

door so he can get at Mina; the shot of her doing so is done with her in

complete shadow. I've already noted how utterly surreal the scene at Borgo Pass looks, and that's to say nothing of the dark cinematography at Castle

Dracula, the scene between Dracula and Renfield in the Vesta's hold, the shadow of the dead captain after the ship reaches England, as well as Renfield's advancing shadow in one scene, which are the definition of Expressionism, and how dark and shadowy the scenes of Dracula preying on people in London are. Speaking of which, in the scene between Mina and Lucy before Dracula makes his move on the latter, if you look in the background, you can see that the lamp against the wall is casting a shadow similar to his silhouette.

Besides the lighting, Freund, who'd virtually invented the concept of the moving camera back in Germany, also does some great work it here, such as the slow, creepy pan through Castle Dracula's crypt to the Count's coffin, as well as towards him the first time he appears onscreen; a shot following Dracula as he walks the streets of London; an interesting bit in the Royal Albert Hall where the camera pans from the box where Dr. Seward, Harker, Mina, and Lucy are sitting, over to Dracula,as he's led to the back of their box, showing how unaware they are of the approaching danger; and a big crane shot establishing the Seward Sanatorium.

Dracula, the scene between Dracula and Renfield in the Vesta's hold, the shadow of the dead captain after the ship reaches England, as well as Renfield's advancing shadow in one scene, which are the definition of Expressionism, and how dark and shadowy the scenes of Dracula preying on people in London are. Speaking of which, in the scene between Mina and Lucy before Dracula makes his move on the latter, if you look in the background, you can see that the lamp against the wall is casting a shadow similar to his silhouette.

Besides the lighting, Freund, who'd virtually invented the concept of the moving camera back in Germany, also does some great work it here, such as the slow, creepy pan through Castle Dracula's crypt to the Count's coffin, as well as towards him the first time he appears onscreen; a shot following Dracula as he walks the streets of London; an interesting bit in the Royal Albert Hall where the camera pans from the box where Dr. Seward, Harker, Mina, and Lucy are sitting, over to Dracula,as he's led to the back of their box, showing how unaware they are of the approaching danger; and a big crane shot establishing the Seward Sanatorium.

Freund is often credited as having been an unofficial second director, with some even going as far as to say that everything great about Dracula is his work, while all of its shortcomings are attributed to Tod Browning. As I said in the beginning, some of the cast described Browning as coming off as lackadaisical, even totally disinterested, on set, with Freund acting more like the actual director. If you've seen some of Browning's other movies, like the silent ones he

did with Lon Chaney or Freaks, you'd know that he could be a good, if not great, director, one adept at exploring the dark and the macabre. He was certainly great at atmosphere, and while many would still credit Dracula's effective moodiness to Freund's cinematography, I can't imagine Browning not having some say in it. And whether or not he was ever truly comfortable with sound and the new technical issues that came with it, his expertise with silent films may have, intentionally or not, led to the movie's eerily quiet nature, making the

sounds you do hear, most notably the howling wolves, much more effective and contributing all the more to its atmosphere (the lack of a music score wasn't Browning's doing, though, as most early talkies didn't have them). But, all that said, there are a number of instances where it feels like Browning didn't try as hard as he could've or just didn't care.

did with Lon Chaney or Freaks, you'd know that he could be a good, if not great, director, one adept at exploring the dark and the macabre. He was certainly great at atmosphere, and while many would still credit Dracula's effective moodiness to Freund's cinematography, I can't imagine Browning not having some say in it. And whether or not he was ever truly comfortable with sound and the new technical issues that came with it, his expertise with silent films may have, intentionally or not, led to the movie's eerily quiet nature, making the

sounds you do hear, most notably the howling wolves, much more effective and contributing all the more to its atmosphere (the lack of a music score wasn't Browning's doing, though, as most early talkies didn't have them). But, all that said, there are a number of instances where it feels like Browning didn't try as hard as he could've or just didn't care.

Despite the aforementioned instances of fluid and innovative camerawork, especially during the first act, on the whole, the camera doesn't move very often. In fact, there's evidence that was more camera movement indicated in the script, as well as that Freund made some suggestions about it to Browning, but the director ignored them. There are a number of moments where a pan, zoom, or even a cut to a close-up would be beneficial, such as in the scene where the passing police officer stops outside the gates of some sort of establishment when he hears the child crying. Never does it cut to a close-up of the cop investigating or even going through the gates and finding the child; instead, it stays on this one, wide establishing shot of the gates, before cutting to Lucy walking away. Therefore, you never learn what that place was exactly. I always thought it was an orphanage or something similar, but it could also be a cemetery where Lucy lured the child in order to bite her. In fact, if it weren't for the following scenes, talking about how Lucy is stalking around at night, preying on children, you wouldn't even know what was going on. Another example is when Dracula, in bat form, flies above Mina on the terrace and communicates with her, all while Harker tries to shoo him away. By this point, you know that he's begun to corrupt Mina, and when she repeatedly says, "Yes? Yes? I will," you can guess that she's responding to his commands, but the way it plays out in one long, static shot ,and hangs on it even

after Dracula has flown off, really makes it feel a little too much like a stage play. Speaking of which, even though there's camera movement here, the earlier scene between Mina, Harker, and Van Helsing out on the terrace, discussing how Lucy is now a vampire, is done in one long, three minute shot, with the camera zooming in from the inside to the terrace, staying on Mina sitting on a sofa for a long time, and then coming back in when the characters do. It also has some bad staging and blocking, with Van Helsing having his back to the camera for much of it, Harker walking offscreen for a while and then coming back, then Van Helsing getting up and walking offscreen, only to speak to Mina a few seconds later to warn her to come inside. But when it comes to bad staging, the most egregious example is when Dracula first meets Dr. Seward and the others at the Albert Hall. Dracula is filmed as he talks with Seward from outside the box, and a step lower, making it look as though Seward is towering over him! Not a great look for your terrifying villain.

after Dracula has flown off, really makes it feel a little too much like a stage play. Speaking of which, even though there's camera movement here, the earlier scene between Mina, Harker, and Van Helsing out on the terrace, discussing how Lucy is now a vampire, is done in one long, three minute shot, with the camera zooming in from the inside to the terrace, staying on Mina sitting on a sofa for a long time, and then coming back in when the characters do. It also has some bad staging and blocking, with Van Helsing having his back to the camera for much of it, Harker walking offscreen for a while and then coming back, then Van Helsing getting up and walking offscreen, only to speak to Mina a few seconds later to warn her to come inside. But when it comes to bad staging, the most egregious example is when Dracula first meets Dr. Seward and the others at the Albert Hall. Dracula is filmed as he talks with Seward from outside the box, and a step lower, making it look as though Seward is towering over him! Not a great look for your terrifying villain.

Besides these technical qualms, there are, indeed, plotholes in the story, like Lucy's subplot never getting resolved, Dracula's brides still being active back in Transylvania, and Renfield approaching the unconscious maid, seemingly about to attack her. Speaking of the latter, while you may think he killed her and then hid the body, she appears throughout the rest of the film, perfectly fine, making the scene all the more pointless, even if the way Renfield slowly crawls towards her is freaky.

Whether it was Browning himself who made these cuts or the studio (again, possibly the latter, as Browning did not have final cut), and for whatever reason, they do leave some unanswered questions. And for me, all of the film's faults come to bear in the ending. First, there's the transition from the scene inside the house, where Briggs, under Dracula's power, lets him in so he can get at Mina, to the exterior, where Van Helsing and Harker, who are randomly standing out there together, see

Renfield heading for Carfax Abbey. It's very jarring and clumsily edited, as is the next cut, revealing that Dracula and Mina are already at the abbey. Second, there's Dracula's fatally stupid mistake, which I've already talked about. Third, while I'm fine with not actually seeing Dracula's staking onscreen, this is where I feel the lack of music and the slow pace does hurt the film, as there's no energy to this finale at all. And finally, the ending is anticlimactic and abrupt. After Dracula is dead and Harker has found Mina, the two of them leave, while Van Helsing stays behind, for whatever reason. Harker and Mina head up the stairs, out of the Abbey, and that's it. The movie is simply over, with no music even on the final "THE END" title card, causing you to go, "Oh, well, okay." A number of these flaws and plotholes are corrected in the Spanish version that was filmed at the same time, which, as well as because of its technical superiority, is often cited as the better film (we'll discuss that movie tomorrow).

Whether it was Browning himself who made these cuts or the studio (again, possibly the latter, as Browning did not have final cut), and for whatever reason, they do leave some unanswered questions. And for me, all of the film's faults come to bear in the ending. First, there's the transition from the scene inside the house, where Briggs, under Dracula's power, lets him in so he can get at Mina, to the exterior, where Van Helsing and Harker, who are randomly standing out there together, see

Renfield heading for Carfax Abbey. It's very jarring and clumsily edited, as is the next cut, revealing that Dracula and Mina are already at the abbey. Second, there's Dracula's fatally stupid mistake, which I've already talked about. Third, while I'm fine with not actually seeing Dracula's staking onscreen, this is where I feel the lack of music and the slow pace does hurt the film, as there's no energy to this finale at all. And finally, the ending is anticlimactic and abrupt. After Dracula is dead and Harker has found Mina, the two of them leave, while Van Helsing stays behind, for whatever reason. Harker and Mina head up the stairs, out of the Abbey, and that's it. The movie is simply over, with no music even on the final "THE END" title card, causing you to go, "Oh, well, okay." A number of these flaws and plotholes are corrected in the Spanish version that was filmed at the same time, which, as well as because of its technical superiority, is often cited as the better film (we'll discuss that movie tomorrow).

Though no original music was composed for Dracula, the opening credits famously feature an excerpt from Swan Lake, which later became something of a motif for Dracula himself in popular culture, as well as for Bela Lugosi in the movie, Ed Wood (though it also played during the credits for both Murders in the Rue Morgue and The Mummy). For a long time, there was a distortion in the music during the section before Tod Browning's directing credit, but it was fixed when the movie was restored for its Blu-Ray release in 2012 (they did a great job with the restoration in general, making the film look absolutely beautiful, and also toning down a constant hiss that's plagued every home media version of it). Also, when Dracula first enters the Albert Hall, you hear the overture to Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg, and just before the scene ends, as Dracula smiles evilly at Lucy, you hear the beginning of Franz Schubert's Unfinished Symphony. And finally, at the end of the movie, as Mina and Harker walk up the stairs and out of Carfax Abbey, you can vaguely hear the sound of bells but, again, there's no music even during "THE END" credit.

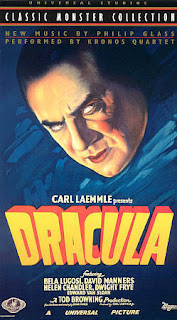

In 1998, Universal commissioned composer Philip Glass to create a score for the film for a re-release on VHS and its debut on DVD, as part of the "Classic Monsters Collection." I remember seeing advertisements for this edition of the film, along with that entire collection, on various Universal releases I got on video around that time, like other Universal Horrors and the "Alfred Hitchcock Masterpiece Collection." They played a little bit of Glass' score during the advertisement, but I never bought that version on video, and even when I did get the movie on DVD as part of the Universal Legacy Collection, I never watched it with the score, save for when I saw a tiny bit of it on AMC one night. I finally did watch it in preparation for this review and it's... fine for what it is, although I see no point in doing this. Performed by the San Francisco-based Kronos Quartet, it plays like a silent movie score, often constantly running under the action and dialogue, though only occasionally reacting to it, like when Dracula sees Renfield's bleeding finger. In general, the music, which also replaces Swan Lake during the opening credits and the Unfinished Symphony, overwhelms this low-key, subtle movie and badly hurts the atmosphere. Sometimes, the music doesn't fit what you're seeing, as the journey aboard the Vesta sounds way too cheerful, as does one of the moments where Dracula rises in Carfax Abbey. That said, they come up with a plucking string motif for Renfield that I think suits his insane character very well. In the end, while it made for an interesting new way to view the movie, I doubt I'll ever watch this version again.

.jpg)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

%20Welcome%20to%20the%20movies%20and%20television.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment